Displaying items by tag: trees

Hornsby Council News

Call for Review of 10/50 Legislation

At their meeting on 11 July, council resolved:

- to write to the state government calling for a formal review of the 10/50 Clearing Code

- to present a motion for consideration at the NSW Local Government Conference calling for a formal statewide review of 10/50

The request is being made on that basis that:

… as the formal review was commenced following only two months of the scheme's operation, rather than two years operation as was the original intent of the legislation, it is questionable whether the review assessed the full impact of the 10/50 scheme over time.

The scheme commenced in August 2014.

The mayoral minute calling for the review argued that there is continuing community and councillor concern regarding the integrity of vegetation clearing being undertaken under the 10/50 entitlement scheme, and the ongoing loss of trees in 10/50 entitlement areas appear to have little to do with bushfire risk or hazard reduction. It pointed out that reversing the decline in tree canopy is a key objective of the Greater Sydney Commission and the clearing code is in conflict with council’s objective to plant 25,000 trees over the next two years.

Let’s Plant 25,000 Trees

The mayor, Philip Ruddock, continues his efforts to improve the tree coverage of the Hornsby Shire to make amends for losses over recent years.

$1 million has been allocated from the budget to plant 25,000 trees by September 2020. Details and a tally of trees planted are provided on http://trees.hornsby.nsw.gov.au.

Council is calling on the community to help plant these trees on special tree planting days and to nurture them as they grow.

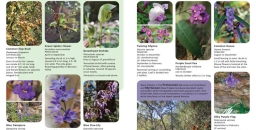

A key source of the new trees will be council’s Community Nursery, 28–30 Britannia Street, Pennant Hills, where production is shifting to a new level. There is an event on 23 September when residents of Hornsby Shire can collect four free native plants.

John Martyn’s New Book, Rocks and Trees

The perfect way to learn about the geology that underpins the landscape and diverse flora of the Sydney region

A photographic journey through the rich and varied geology, scenery and flora of the Sydney region

Rocks and Trees captures the dramatic scenery of the Greater Blue Mountains, the beauty of the coastline and the great sweep of plains west of the CBD, but its main purpose is to highlight the geology and flora and their interrelationships. The book journeys from the Illawarra along the coast to Newcastle and inland to the Greater Blue Mountains, staying within the framework created by the massive sandstones and conglomerates of the Triassic Narrabeen Group.

Tree Bonds can help Preserve the Urban Forest

Great cities need trees to be great places, but urban changes put pressure on the existing trees as cities develop. As a result, our rapidly growing cities are losing trees at a worrying rate. So how can we grow our cities and save our city trees?

Tree bonds have recently been proposed by Stonnington City Council as a way to stop trees being destroyed in Melbourne’s affluent southeastern suburbs.

Tree bonds are a common mechanism for protecting trees on public land, but have so far had limited use on private land. A tree bond requires a land developer to deposit a certain amount of money with the local authority during development. If the identified tree or trees are not present and healthy after the development, the funds are forfeited.

The size of the bond can be established based on estimated tree replacement costs, and/or set at a level that is likely to achieve compliance (likely to be thousands or tens of thousands of dollars).

Why are trees important in cities?

The concept of an 'urban forest' includes all the trees and plants in cities. This includes tree-lined city streets as well as parks, waterways and private gardens. The urban forest contributes substantially to the quality of life of all urban dwellers, both human and non-human, and is increasingly used to adapt cities to climate change.

Trees cool the streets, filter the air and stormwater, and create a sense of place and character. They provide food and shelter for insects, birds and animals.

There is growing research evidence for the physical, mental and social health benefits of urban trees and green spaces. Many local councils such as Brimbank and Melbourne are investing substantially in tree planting to increase these benefits.

However, despite new tree planting on public land, tree canopy on private land is declining.

What can we do to protect trees?

There are a range of existing policy and land use planning measures focused on landscaping requirements for new development. Recently, the Victorian government introduced minimum mandatory garden area requirements. Some Melbourne councils, including Brimbank and Moreland, have also included planning scheme requirements for tree planting for multi-dwelling developments.

Other mechanisms for protecting urban trees on private land include heritage and environmental overlays within local planning schemes, and listings of significant trees and heritage trees.

However, penalties, monitoring and enforcement of tree protection bylaws have not kept pace with the pressures of urban change.

If penalties are insignificant relative to development profits, developers can easily absorb the costs. If monitoring is weak and removal has a good chance of going undetected, tree protection is more likely to be ignored. And if enforcement is weak, or there is a history of successful appeal or defeat of enforcement, many trees may be at risk of removal.

Even when it is successfully pursued, after-the-fact planning enforcement action is a particularly unsatisfactory recourse for tree removal. Replacement trees may take decades to match the quality of mature trees that were removed. What is needed, then, are mechanisms that prevent tree removal in the first place.

Increasing use of tree bonds

The advantage of tree bonds is that they place the onus of proof of retention on developers, rather than the onus of proof of removal on local councils. If a tree is removed, the mechanism is already in place to monitor (the developer needs to demonstrate the tree is still there) and penalise (the financial penalty is already with the enforcing body).

However, tree bonds still do not guarantee tree protection. Some mechanisms used to impose tree bonds may be vulnerable to challenge. For example, historically in Victoria, the planning appeals body VCAT has struck out conditions imposing tree bonds, arguing that punitive planning enforcement measures should be used where trees are removed.

Even where bonds can be imposed and enforced, developers may still be able to demonstrate that trees are unsafe or causing infrastructure damage, and thus need to be removed. In these circumstances, it is often hard to prove otherwise once the tree has been removed.

Nurturing an urban forest

Ultimately, if a landowner is hostile to a tree on their land, that tree’s health and survival can be imperilled, whether through illegal removal, neglect, or applications for removal based on health and safety grounds. It is therefore important that building layout and design realistically allow space for trees to flourish and be valued by landowners.

The urban forest needs protecting and enhancing. This calls for a range of policy mechanisms that work together to retain mature trees, maintain adequate spacing around them, and encourage residents to value and protect the trees around their homes.

![]() Tree bonds provide an attractive solution for local governments in the absence of a strong land use policy framework for protecting trees.

Tree bonds provide an attractive solution for local governments in the absence of a strong land use policy framework for protecting trees.

Joe Hurley, Senior Lecturer, Sustainability and Urban Planning, RMIT University; Dave Kendal, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Management, University of Tasmania; Judy Bush, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub, University of Melbourne, and Stephen Rowley, Lecturer in Urban Planning, RMIT University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Quick Response to Loss of Trees in Hornsby

In the previous issue of STEP Matters we reported on the major loss of trees in Hornsby Shire in recent years and the commissioning of a report by council outlining options to strengthen tree protection measures to re-establish Hornsby’s tree canopy.

In December council put forward a draft amendment to the tree preservation provisions of the Development Control Plan. The amendment, if enacted, would make the tree preservation order similar to the rules that apply in Ku-ring-gai. Council approval would be required for the removal or significant pruning of all trees except listed weed species.

This a major turnaround from the current situation where trees can be removed except if they are on the list of local indigenous species or in a heritage area.

Submissions closed on 26 January. We hope the amendment will be adopted promptly.

Extraordinary Loss of Trees in Hornsby

Hornsby Council weakened its Tree Preservation Order (TPO) in 2011 so that only tree species indigenous to the area (about 100 species) are protected apart from heritage conservation areas where all trees (as defined in the TPO) are protected. In June 2014 we wrote about a survey of tree cover that revealed that about 2% of the area was lost during 2011-13, about 27% more than the previous 2 years (see STEP Matters, Issue 176, p3). This data was recorded before the 10/50 bushfire clearing regulations came into force plus the tremendous number of new apartment approvals and infrastructure development.

Now the new mayor, Philip Ruddock has expressed shock at the latest data showing that 15,000 trees were cleared in the last year which equates to 60 hectares of canopy. The council has commissioned a report outlining options to strengthen tree protection measures to re-establish Hornsby’s tree canopy.

It is hard to get clear data of the tree cover in Hornsby because about two-thirds of the Shire’s tree cover is in national parks and reserves. Some reports do not make it clear whether they were looking a percentage loss of tree canopy in the total area or just urban areas.

In 2014, 202020 Vision (a collaboration of horticultural companies formed with the objective of making our urban areas 20% greener by 2020) published the Where Are All The Trees? report based on research undertaken by the Institute of Sustainable Futures at UTS Sydney. This was the first time that urban canopy had been benchmarked nationally.

This year, RMIT and Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub researchers published a follow-up report called, Where Should All the Trees Go? that compares canopy levels, overlays urban heat and socio-economic data, and provides an overall vulnerability indicator.

This report showed that Hornsby had lost 5% of urban tree canopy over the 5 years to 2016. And the latest report is that over 2016-17 the loss was 3%. At the current rate there will be very little urban tree cover left in 30 years’ time.

Loss in Pittwater (13%) and Warringah (7%) over the 5 years was even worse.

Dr Peter Davies pointed out in his talk at our AGM that there are many factors that will make it harder to increase urban tree cover in the future, the main one being the reduction in housing block sizes. The new block sizes of as little as 250 m2 leave no room for a backyard let alone trees. So the main responsibility for tree canopy will fall on local authorities.

Looking down Harwood Avenue, Mt Ku-ring-gai. Before the change to the TPO in 2011 and the introduction of 10/50 in 2015 it was impossible to see the boundary of Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. Now the suburban area is stark against the wall of trees in the national park.

We Need to Fight to Keep our Urban Forests

NSW residents are currently waiting for the state government to respond to the deluge of submissions opposing the new draft biodiversity and land clearing laws. The application of this legislation to Sydney’s bushland is unknown at present.

Urban Forests

Essentially there is a conflict between the need to accommodate the expectation of continuing high population growth and the desire to maintain a desirable city to live in. The high population growth is totally undesirable but we have had plenty to say about that before.

Now turning to the ideal of having liveable cities, one of the major elements is adequate tree cover. This is not impossible to achieve if there is the political will to get the planning right. Given the attitudes of the current NSW government to trees, residents will need to make it loud and clear that they will not accept a continuation of current policies.

In North Sydney Council’s Urban Forest Strategy document 2011, urban forest is defined as:

… the totality of trees and shrubs on all public and private land in and around urban areas and is measured as a canopy cover percentage of the total area. The canopy cover may vary in density depending on the vegetation type (eg almost solid cover under rainforest vegetation to more open cover under woodland or eucalypt forests) however the canopy cover percentage for urban forest measurement purely measures the percentage of land that has tree or shrub vegetation (over 3 m tall) above it, regardless of density.

Benefits of Urban Forests

Reduction in the Urban Heat Island Effect

Heat from the atmosphere is used in vegetation transpiration processes which convert water from leaves to water vapour. This has a cooling effect similar to that when humans perspire. Trees can transpire significant volumes of water and it has been estimated that a mature tree can transpire up to 150 L/day. In a hot dry location this produces a cooling effect similar to that of two air conditioners running for 20 h.

Much of the urban landscape is paved and devoid of vegetation. This means that there is usually little water available for evaporation, so most available natural energy is used to warm surfaces. Construction materials are dense, and many – particularly dark-coloured surfaces like asphalt – are good at absorbing and storing solar radiation.

Trees are a very effective means of blocking the sun’s radiation and, depending on the species and its maturity, up to 95% of the incoming radiation can be blocked. Trees can reduce a building’s temperature by directly blocking radiation through windows and cooling the surrounding air, and can also keep the soil cool thus providing a sink for heat from the building. These effects have been quantified as reducing air temperatures in built up areas by 1 to 5°C.

Reduction in Energy Demand

A typical adaptation response to the lack of external cooling is reliance on air conditioning, which generates waste heat and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Studies in the US have indicated that 5 to 10% of electricity demand in cities is from air conditioners used to compensate urban heat island effects. Increases in peak energy demand drive up infrastructure costs and increase the risk of power cuts during heatwaves. Air conditioner use amounts to nearly one-third of the power consumed in Perth on the hottest days in February and March.

Other Benefits

- Reduction in water run-off and erosion during storm events

- Improvement in water quality as the slowing of water run-off allows particulate matter to precipitate out and not pollute waterways

- Wind mitigation

- Improvement in air quality by absorbing gaseous pollutants and trapping particulate matter on their leaves

- Storage of carbon

- Reduction in noise pollution

- Shade for parked cars and outdoor pursuits

- Visual amenity and privacy

- Improved property values

- Attraction of birds and habitat for other wildlife

Recommended Canopy Cover

There have been many international studies of recommended canopy cover targets for urban forest. For example, according to the North Sydney report, for this climatic zone the recommended percentages for specific land-use areas are:

- 15% cover in central business districts

- 25% cover in medium and high density residential areas

- 50% cover in low density residential areas

Many cities now have urban forest targets in place, for example:

- Sydney city aims to increase urban forest cover (including private land) by 50% by 2030 and 75% by 2050

- Melbourne aims to increase canopy cover from 22 to 40% by 2040

- London aims to increase urban tree cover from the current 25% to 32% by 2065

- In 2015 New York City achieved a goal of planting one million trees to increase its urban forest by 20%

- Australian government has pledged to develop decade-by-decade goals out to 2050 for increased overall tree coverage

In 2014 the Institute for Sustainable Futures documented the tree cover in various parts of Sydney: Hornsby (59%), Ku-ring-gai (52%), Blacktown (19%), Parramatta (23%), City of Sydney (15%) and Rockdale (12%).

The figures for Hornsby and Ku-ring-gai are distorted by the inclusion of national parks that can provide some regional benefits such as improved air quality and cooling breezes if the wind is blowing in the right direction. However they do not provide the same benefits associated with trees in the immediate vicinity.

Stumbling Blocks

There are many barriers to achieving and maintaining urban forest. Generally the larger the trees the more effective are the benefits listed above. However there is a cost with managing larger trees. Trees ultimately need to be replaced when they reach their useful life expectancy. In an urban environment one cannot allow trees to reach the age where they become dangerous. There is also the need to achieve access for solar panels.

Developers will argue that the land is worth much more if it is built on. As we have seen all too often in Sydney, house blocks that had room for gardens, now have high and medium density housing with minimal, if any, tree cover remaining. SEPP65, the planning policy for high-rise is supposed to provide for deep soil planting but it does not seem to be enforced.

SEPP65, the planning policy for apartments covering all of NSW, now has a minimum deep soil requirement of only 7% of site area (Apartment Design Guide, p61). This is totally inadequate for a high rainfall area such as the North Shore where the native trees can reach heights of 30 m or more. Ku-ring-gai Council requires a minimum 50% site area for deep soil landscaping on sites over 1800 m2. This should be maintained and not over-ridden by SEPP65 Apartment Design Guide requirements.

Tiny backyards in new fringe areas and boundary-to-boundary development of new houses in existing suburbs often eliminate private land’s potential contribution to the urban forest. This puts incredible pressure on the public realm to provide the urban forest on top of needing to meet demands for infrastructure.

Compact city land-use policies and urban forest policies need to work together to ensure that cities have high-quality built environments and extensive tree cover. These policies must set the overall goals and outline strategies to deliver on them for both public and private land.