Displaying items by tag: water catchment

How Should the Flood Risk from the Hawkesbury Nepean be Managed?

The NSW government thinks that raising the spillway wall of Warragamba Dam by 14 m will significantly reduce the risk of floods inundating homes in western Sydney. But experts have questioned whether the raising will achieve worthwhile benefits and whether the ecological damage can be acceptable. They argue the water levels in the dam storage should be better managed instead.

Brief History of Sydney’s Water Supply

The first water supply dams built to supply Sydney were the Upper Nepean dams (such as Avon and Cataract Dams) that still provide 20-40% of our supply. When this supply became inadequate the next step was the construction of Warragamba Dam that commenced in 1948 and was completed in 1960. The resulting storage in Lake Burragorang is one of the largest reservoirs for urban water supply in the world.

Following 1988 and 1989 high rainfall years, the NSW government re-evaluated the potential rainfall and flood risks and raised the dam wall by 5 m and constructed an auxiliary spillway on the east bank of the dam.

Back in February 2007 the Warragamba Dam water supply fell to its lowest recorded level of 32.5% after the prolonged drought from 1998. In response conservation measures and water usage restrictions were introduced. The desalination plant was built at Kurnell but this has hardly been used as we have had a period of above average rainfall ever since. Now the concern is flood risk. In 2012 and 2015 water had to be released to prevent a mass overflow. Currently the level is around 91%.

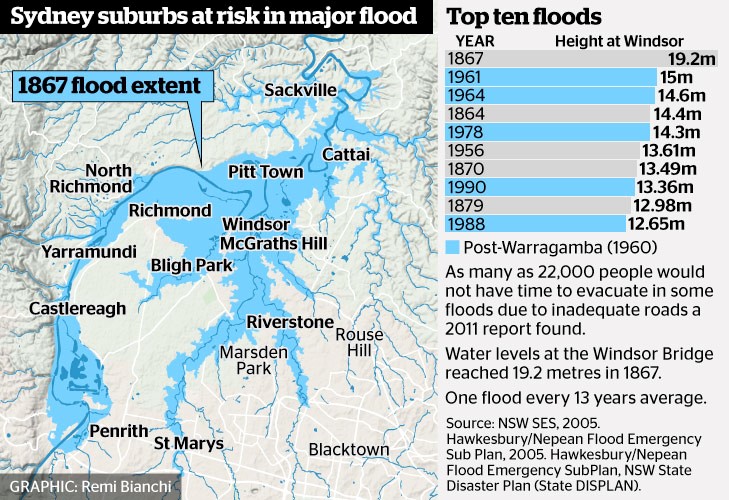

The benchmark for flood risk often used is the worst recorded flood that occurred in 1867 when the water height at Windsor Bridge was 19.2 m. This figure (from Sydney Morning Herald) provides data of past major floods and the flood extent in 1867.

The benchmark for flood risk often used is the worst recorded flood that occurred in 1867 when the water height at Windsor Bridge was 19.2 m. This figure (from Sydney Morning Herald) provides data of past major floods and the flood extent in 1867.

According to the State Emergency Service, the estimated rainfall in 1867 in the lead up to the flood was 770 mm over three days averaged over the entire Nepean River catchment. The flood experience would be different now because several dams have been built in the Nepean catchment.

Government Proposals for Flood Mitigation

The high rainfall experienced in 2013 led to the need to release water causing minor flooding. The NSW government initiated another Hawkesbury Nepean Flood Management Review.

The review concluded that there is no simple solution or single infrastructure option that can address all of the flood risk in the Hawkesbury Nepean Valley floodplain. The risk will continue to increase with population growth. Evacuation is the only mitigation measure that can guarantee to reduce risk to life. According to the State Emergency Service a flood at the 1867 level would now lead to the evacuation of 90,000 people, damage to 12,000 homes and a cost of $5 billion.

As Prof Paul Boon explained during his STEP talk on 11 July on the Hawkesbury River, the topography of the river valley creates several challenges in understanding and managing flood risk.

The Hawkesbury has two main sources, the huge catchment of rivers that flow into Warragamba Dam that has its own flood plain from Emu Plains to Castlereagh. Then the Hawkesbury starts at Yarramundi when water sourced from the Grose Valley catchment in the Blue Mountains joins the Nepean. There is a flood plain around Richmond and Windsor through to Cattai but then more rivers join in and the valley narrows again with steep sandstone gorges and many twists and turns. This means that floods can bank up and spread out over broad areas of western Sydney.

Recommendations of the Review

Some points from the first review report are:

- Due to time constraints the review only assessed the flood mitigation potential of raising of the Warragamba Dam wall crest by 15 and 23 m. Pre-feasibility construction costs and reduction of flood levels have been calculated. However, economic, environmental and social costs and benefits have not been included at this stage. Detailed cost benefit analysis will be conducted for the options for the raising of Warragamba Dam in Stage 2 of the review.

- The review also assessed the potential for changing the operation of Warragamba Dam at its current configuration to provide for flood mitigation. Options examined different ways to create airspace to capture a portion of incoming floodwaters, by reducing the full supply level of the dam, ‘pre-releasing’ water if major flood inflow are expected based on forecast rainfall, or ‘surcharging’ the dam level during floods using the dam’s gates.

- The review concluded that only minor floods, below levels where significant damages occur, could be mitigated using the current dam unless its role as the main water supply to Sydney was compromised. It was also concluded that ‘pre-releasing’ of water from the dam prior to a flood was limited due to the inaccuracies in rainfall forecasts beyond three days, and the potential to increase or prolong downstream flooding.

- Reducing the full supply level of Warragamba Dam provides only a reduction in minor flooding and needs to be assessed against the impacts on Sydney’s water supply. The review considered lowering the full storage level by 2, 5 and 12 m, and concluded that the 2 m lowering had minimal flood mitigation benefits, and the

12 m lowering would have significant impacts on Sydney’s water supply. - Stage 2 of the review will further analyse surcharging the gates and reducing the full supply level for the mitigation of smaller floods, including the operational risks and the impact on Sydney’s water supply.

Even though Stage 2 of the review has not been completed, WaterNSW has been preparing environmental impact statements based on a proposal to raise the dam wall by 14 m and made a referral under the Federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act on specific matters of national environmental significance.

The intended operation after the spillway wall is raised is for water to be held back during a heavy rainfall event and then released slowly in the following weeks. This will provide additional time for evacuation and reduce the downstream flood peak. The stated intention is not to increase the current overall water storage level.

Environmental Impacts

The Colong Foundation for Wilderness has expressed serious concerns about the impact of the current proposals. The fundamental points made in their Colong Bulletin (July 2017) are:

The Colong Foundation for Wilderness has expressed serious concerns about the impact of the current proposals. The fundamental points made in their Colong Bulletin (July 2017) are:

- Raising the dam level does not deal with the flood waters coming from the major rivers further downstream such as the Grose, Macdonald and Colo.

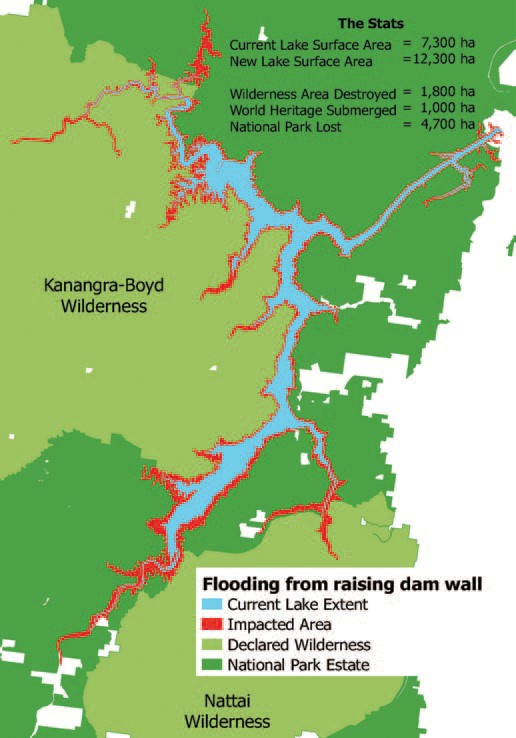

- The extra water storage is intended to be temporary but the vegetation around Lake Burragorang and its tributaries that will, nevertheless, be flooded for several weeks will die leaving ugly scaring of the banks. The upstream flooding will impact the Kedumba and Colong River valleys that are part of the World Heritage listed wilderness areas. A further 1800 hectares could be flooded and another 33 km of rivers inundated.

- The backed up water in the Kedumba River will be visible from Echo Point, the iconic lookout in the Blue Mountains at Katoomba. The figure illustrates the projected increase in areas affected by inundation.

- Even flooding from a 1 in 50 year flood will extend 5 km into the Kedumba Valley and cause the death of 40% of the critically endangered Camden White Gum Forest. This species is listed as vulnerable under the Threatened Species Conservation Act. The Department of the Environment includes the forest in the Kedumba Valley as part of the Save Our Species biodiversity restoration program with an objective ‘to secure the species in the wild for 100 years and maintain its conservation status under the TSC Act’. Methinks WaterNSW should talk to the Department of the Environment.

- Aboriginal cultural heritage will be destroyed.

- Classic bushwalking areas will be lost, historic campsites drowned and access restricted. Bushwalkers are drawn to the pristine Kowmung River, a wild river that has inspired generations of walkers.

Can the Water Storage Level be Managed Instead?

Assoc Prof Stuart Khan, an expert in water engineering, disagrees with the need to raise the dam level. Management of the water level by controlled releases is a safer option so that the dam is never full. The desalination plant that can supply 15% of Sydney’s water needs, could be put to use when the need arises by way of earlier releases. Basically he disagrees with the review’s conclusions.

This is a fascinating risk management problem. Should we:

- reduce the water level if a period of heavy rainfall is projected and thereby reduce the water supply capacity with the backup of the desalination plant; or

- increase the dam wall at great expense and environmental damage that would threaten the tourism industry but still not eliminate the flood risk

Whatever option is taken flood risk cannot be eliminated. However the government is still going ahead with allowing massive population increase in the flood plains of the Hawkesbury Nepean system. As population grows the warning time needed to organise evacuation will increase.

Given the improvement in longer term weather forecasting. The government must explore options for smarter use of risk management techniques to adjust the storage levels. Raising the dam wall ignores this potential and could be a waste of $700 million.

Also future governments could easily be tempted to use the raised dam wall to increase water storage permanently to provide water supply for Sydney’s projected massive increase in population.

Other Serious Water Management Issues

As reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on 21 August, coal mining is impacting on the Sydney water supply catchments but the government is not carrying out adequate monitoring.

The 2016 Audit of the Sydney Drinking Water Catchment was tabled in parliament on the quiet. The National Parks Association discovered the report. It revealed that groundwater losses from longwall mining under the catchments in the Woronora areas has not been quantified. This is despite mining company reports have indicated that about 25 to 40 million litres a day have been entering the mines.

The 2013 audit report revealed that research was underway into the connectivity of surface and groundwater but no results have been revealed in the 2016 audit. This is not good enough given that these mining companies are still applying to expand their mining operations under the catchment.

There are also problems with coal mines leaking toxic chemicals into catchment rivers. Examples are the Springvale mine that has been pumping untreated waste into the Coxs River and the closed Berrima mine that has been leaking pollutants into the Wingecarribee River.

Longwall Mining in Sydney’s Water Catchments

The battle continues against coal mining under the water catchments in the Illawarra but there are some hopeful signs that the NSW Government could start to see sense about the environmental damage that is occurring.

Sydney is fortunate to have a pristine water supply on its doorstep. In theory the water catchments are protected as development and agriculture are prohibited. In the Special Areas in the Illawarra catchment anyone entering the land without permission can be fined $44,000. These catchment areas contain bushland and natural systems such as coastal upland swamps that slow water movement and filter the water that flows into dams such as the Avon and Cataract. Many other cities have to pay millions of dollars to operate synthetic filtering systems of their water supply.

Mining has been undertaken in the Illawarra region since the 1880s but in the early days the methods used were pick and shovel and later machinery that took out small sections of the coal seam. The mine ceilings and walls were supported by the bord-and-pillar method. Since the 1960s the technology for longwall mining has been developed that vastly increases the rate of removal of coal and, incidentally, cuts the level of employment significantly.

The coal is removed by a massive machine that shears away the wall beside it whilst hydraulic powered supports hold up the roof. As the coal is removed, the machine supports are moved forward and the roof is collapsed behind them. The areas of rock extracted are 150 to 400 m wide, 4 m high and can extend for several kilometres. When one longwall is completed another is started leaving a rock support of about 50 m in between.

As such a large section of coal is removed the roof above the longwall collapses. Depending on the nature of the rock above, minor cracking can occur in the strata above, but frequently major cracking has occurred right up to the surface. Cracking leads to water leaking from the creeks and wetlands, pollution from the release of excess minerals from the underlying rocks and cliff falls.

Concerned locals have been documenting the damage over the past ten years and have been leading a campaign to raise awareness of the damage and making detailed submissions explaining the concerns about current and future development applications. This group was formalised by the creation of the Protect Sydney’s Water Alliance in 2013, a network of more than 50 community groups from across Sydney, the Illawarra, Southern Highlands and Blue Mountains.

Illawarra Mines

The Illawarra mines all produce coal for steel making. They make up a complex array of cavities under a region that has reliable rainfall and therefore is a significant source of drinking water for Sydney as well the large population of the Wollongong region. The main miners are:

- Wollongong Coal Ltd, listed on the ASX but majority owned by Indian company Jindal Steel and Power, with mines at Russell Vale near Cataract Dam and Wongawilli further south. The Russell Vale mine has run out of approvals. The Wongawilli mine was suspended but the company has now applied to extend its licence and reopen the mine.

- Illawarra Coal owned by South32, a company demerged from BHP that operates the Dendrobium mine near the Avon Dam.

- Peabody Energy operates the Metropolitan mine near the Woronora Dam.

There are two current controversial applications for extension of current mining operations.

Wollongong Coal

In Issue 180 of STEP Matters we wrote about the Planning Assessment Commission’s (PAC) report on the application to develop eight new longwalls. Wollongong Coal failed to convince PAC that it can expand the Russell Vale colliery without causing substantial and irreversible damage to Sydney’s drinking water supply.

As the mining approvals have run out the mine was closed six months ago, and the entire workforce was sacked. But the company seems undaunted and has continued with the expansion application.

The second review of the mine expansion by PAC has just been released and has reinforced the previous opinions. Despite acknowledging the short-term benefits of the project – which includes the provision of 300 jobs for five years, about $23 million in royalties to the NSW Government and $85 million in capital expenditure and other direct and indirect flow-on effects – PAC concluded that:

On the basis of the information provided, the Commission is of the view that the social and economic benefits of the project as currently proposed are most likely outweighed by the magnitude of impacts to the environment.

In particular, PAC identified the risk of water loss, risk to upland swamps, noise impacts on nearby residents, potential hydrogeological impacts and a loss of ecosystem functions.

PAC is not satisfied that the project is consistent with the State Environmental Planning Policy (Sydney Drinking Water Catchment) 2001 that it would have a neutral or beneficial effect on water quality in the catchment area. The magnitude of water loss is uncertain with the projected range from the proponent and Water NSW varying from minimal to 2.6 GL/year. PAC considers this is a high risk situation. Sydney Water has valued the potential water loss at a cost of $23 million over 25 years. The cost of government subsidies are also estimated to be $23 million. The expansion is economic as well as environmental madness.

A separate issue is the financial viability of the company itself.Wollongong Coal currently has no capacity to repay its debts unless it is thrown another financial lifeline by parent Jindal Steel & Power (Australia) Pty Ltd. The company is currently suspended from trading on the Australian Stock Exchange. If the project falls over the company has no capacity to remedy any damage it could cause to the catchment.

Under legislation passed in 2014 in response to ICAC findings the Minister for Resources can deny a mining application if the proponent is not deemed to be ‘fit and proper’. The Environmental Defenders Office has presented a strong portfolio of evidence that Wollongong Coal fails that test. The minister’s response is so far non-committal. This is the first time a decision is being made under this legislation so it may take a while to consider the precedent it may establish.

The final decision is in the hands of the government.

Dendrobium Mine

The Dendrobium Mine was approved in principle by a Planning Assessment Commission in 2001 and significantly expanded in 2012 despite great concern to those watching the significant damage that had already occurred to every swamp that was above an existing longwall.

The company is now applying for a further expansion closer to Avon Dam. Protect Sydney's Water Alliance objected to the expansion for several reasons:

- proven ongoing damage caused by current longwall mining

- failure by the proponent to take any steps to mitigate damage to swamps in previous longwalls

- failure by the proponent to prove that swamps can be rehabilitated or to undertake agreed research in this area

- the Dam Safety Committee clearly states in its submission that no longwall mining should take within 300 m of the full supply level of Avon Dam (the proposed longwalls will be within 250 m of the dam)

- the cumulative Impact of this mining on the catchments over the long term (as per PAC 2016 rejection of Russell Vale expansion)

- the dubious nature of jobs claims and the lack of any evidence that royalties or bond can ever cover the cost of rehabilitation

The closing date for submissions is 15 April. Click here to make a submission.

Metropolitan Mine

This mine was given approval for major expansion in 2009 despite major damage already occurring to the Waratah Rivulet and failed attempts to remediate the cracks using polyurethane resin injections. Peabody Energy is currently in financial straits because of the fall in the coal price. However, it is expected that the company will apply for a further expansion in the near future.

Significance of PACs Wollongong Coal Report

The issues raised in the PACs report apply to all the other mines in the catchment. It is hoped that heed will be taken of the strong opinions of the report when the current expansion plans of the Dendrobium and, possibly, future Wongawilli and Metropolitan mine expansion applications are considered.

Russell Valley Colliery Expansion Thwarted

Previous issues of STEP Matters (Issue 173, p7–8 and Issue 175, p2) have highlighted the damage that is occurring in Sydney’s southern water supply catchment in the Woronora area caused by underground longwall coal mining. Cracking of the surface has drained upland swamps and creeks that are the filter system and source of water flowing into the Cataract and Woronora dams.