Displaying items by tag: population

Response to housing shortage – will it trash liveability?

High net immigration is putting huge pressure on governments to get more housing built. But do we need to do this at the expense of planning rules that are intended to create housing areas where people might actually enjoy living?

The new NSW government has announced that it will scrap local council and planning panel processes for developments worth more than $75m if they include at least 15% affordable housing. Developers will be able to go straight to the Department of Planning via state significant development rules so that decisions will made more quickly.

Further, these developments will also gain access to a 30% floor space ratio boost, and a height bonus of 30% above local environment plans.

Councils have been assured by the Minister for Planning (Paul Scully) that they will be consulted about the strategic merit of these proposals and council local environment plans will not be overridden.

The reforms are set to take effect later this year and are a part of the government’s commitment to construct 314,000 homes over five years.

Huge growth in population over 2022

It is not hard to see why we need so much new housing. Australia’s population grew by almost half a million during 2022 to reach 26,268,000 people at 31 December 2022. The annual growth was 496,800 people (1.9%). Annual natural increase was 109,800 and net overseas migration was 387,000.

Population – big Australia back on the agenda

The Centre for Population, part of federal Treasury, was established in 2019 to improve data collection on how Australia’s population is changing and the implications of these changes.

The Centre makes an annual statement of population including analysis of changes over the past year. The 2022 statement has recently been released. This report also covers projections of future population levels out to 2033 as well as analysis of the impact of COVID on recent migration and mortality experience. It is good to see regular information in one location instead of previously having to delve into ABS and Department of Immigration website data.

This report brought out the usual hype in the media about the need for new migrants to stave off the ageing population burden and labour skill shortages. There is only limited discussion of the impact the growth will have on significant aspects of social and environmental wellbeing, such as cost of housing and biodiversity.

Projections for next 10 years

The baseline assumption of future net overseas migration (NOM) is 235,000 per annum based on the average over recent years prior to the COVID-19 slowdowns plus some adjustment for policies increasing permanent placements. Despite the COVID experience we are still trying to catch up on the demand for services and infrastructure that was generated by the escalation of growth that was started by the Howard government in 2006 and has been perpetuated by subsequent Labor and Coalition governments ever since. Prior to 2006 NOM was half that level or less.

Our current population is 26.1 million (as at September 2022). The projection in the Population Statement 2022 is that we will reach 30 million by mid-2033. However, the level of migration has been ramped up since the Labor government came to power as a backlog of applications is being processed and international students are flooding back. It is estimated that the NOM for the next two years will be 650,000 so that growth including natural increase (births less deaths) will approach 950,000. No wonder there is a housing crisis! The slowdown during the COVID-19 shutdown is becoming irrelevant.

Intergenerational report — projections to 2060

The 2021 Intergenerational Report provides longer term projections of the outlook for the economy and budget.

This report used the same assumption for NOM of 235,000 pa for the whole 40 years of their projections. The total population in 40 years’ time is projected to be an eye-watering 39 million. That is a 13 million more people, a 50% increase! The growth over the past 40 years was 11 million. We can see the impact of that number. To use the hackneyed catch phrase, it is unsustainable. Liveability of our cities has declined. The State of the Environment Report 2021 showed significant declines in biodiversity. Surveys have highlighted that citizens do not want this high rate of growth to continue.

The governments at state and federal level express plans to stop species extinctions, reduce carbon emissions and improve liveability but they carry on, regardless of popular opinion, doing nothing to stop the forces that go against these policies; vegetation clearing, bigger houses, more roads.

Apparently, there is no contemplation that our growth will ever slow down. The concept of longer term planning whereby the growth can be reduced over time is anathema to the politicians and business even though it would be welcomed by voters. We have to accept the reality of adapting by increasing skill levels, retraining the existing workforce and increasing workforce participation into retirement age. The easy option is still being taken by importing skills from countries that need them more. The hard decisions are being left to future generations.

Alternative viewpoints

Sustainable Population Australia, an environmental advocacy organisation, has recently published some discussion papers with academic analysis calling into question the status quo.

The housing crisis is a population growth crisis

Some of the key points made are:

- The connection between population growth – driven by high immigration – and high housing cost inflation is often ignored or denied in political circles but is accepted as an undeniable fact by almost everyone knowledgeable about the property industry.

- An accumulation of ill-advised policy measures (e.g. negative gearing, reduction in capital gains tax and first home buyer grants) have combined with accelerated population growth to create a perfect housing storm.

- A lower net migration level is needed to slow growth and stabilise population size. Even an optimally regulated market will not prevent housing inflation in the face of endless population growth.

- Lower, well-targeted immigration will not cause intractable skills shortages or unmanageable population ageing, but will reduce housing stress and inequality, and improve environmental amenity.

How many Australians? The need for Earth-centric ethics

This discussion paper has been written by Dr Paul Collins, an historian, broadcaster and the author of 17 books on Catholicism, the papacy, environmental ethics and population issues.

The paper addresses the competing demands of human beings seeking a better life with the rights of our natural systems to prevail against the demands of human activities.

Despite its physical size, Australia is limited in biophysical and geophysical terms. All our State of Environment reports have found the demands of the current population have been degrading natural systems irreversibly. We are not living sustainably with the numbers we have at current standards of living.

Millions want to come and share the riches we enjoy. Do we have a moral duty to let them come and allow them a better life? Or should we protect the ecosystems in our care?

He calls for a totally new moral principle to guide and govern our ethical behaviour as a species. He argues that we must shift our ethics away from anthropocentrism and economism which pays no heed to our dependence on the natural world. Instead, moral decision-making must give priority to the Earth, biodiversity, climate stability and the integrity of natural systems.

The case for degrowth: Stop the endless expansion and work with what our cities already have

Australian cities are good at growing – for decades their states have relied on it. The need to house more people is used to justify expansion out and up, but it is the rates, taxes and duties that flow from land transfers and construction that drive the endless development of Melbourne and Sydney in particular. Property development is the single largest contributor to Victorian and New South Wales government revenues.

For example, the City of Melbourne’s draft spatial plan proposes new suburbs to the west and north. It’s continuing on a course mapped out in the post-recession 1990s, when Australian governments focused on building on or digging up our great expanses. The plan neither questions the rationale for growth nor, apparently, the deeper effects of the pandemic.

The city council is understandably anxious to attract people back to the centre. The city plan presumes a return to Australia’s high population growth of the 2000s. Expectations of a renewed influx of students, workers and tourists from overseas are based more on hope, however, than reason.

The drivers of population growth are more uncertain and we can no longer depend on global mobility at pre-pandemic levels. Birth rates are falling across the developed world, online international education is improving, and research suggests pandemics will persist while cities encroach on the habitats of so many other species.

Meanwhile, the towers thrown up in the heady years of growth are half-empty and cracking, poorly ventilated, reliant on central air conditioning and not built for more extreme weather or low energy consumption. Melbourne and Sydney’s showcase regeneration projects at Docklands and Barangaroo are more dismal and deserted than ever.

Better needn’t mean bigger

Now is not the time for anyone to announce that their city will become “bigger and better”. Cities don’t have to get bigger to evolve, and sooner or later all will have to reckon with the concept of degrowth.

Australia must become less reliant on imports of skilled workers, students, tourists and materials. We can make better use of local resources and produce much more of what we need here.

Australian cities have very good bones. They have amazing cultural scenes. Their biomedical capabilities are among the world’s best. Our education sector remains eminently exportable online and via existing overseas campuses. The manufacturing sector still has a base to build on and provide many more of the products Australians need. And our renewable energy capacity is unlimited.

We can support our local hospitality and cultural venues better, and increase intercity and interstate patronage. We can invest in research and development and maintain wealth through innovation and production, rather than the eternal consumption of land.

Rethink what we build and why

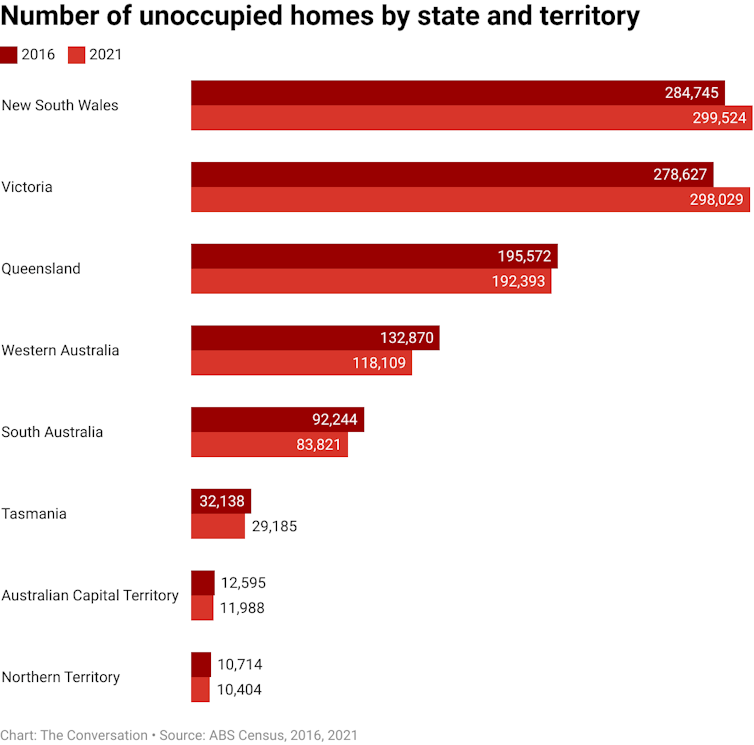

Adapting to global environmental conditions means rethinking not just what and how we build, but why. Before designating land for yet more housing estates, for example, let’s consider that a million homes – 10% of Australia’s housing stock – were empty on census night last year. Nearly 600,000 were in Victoria and New South Wales.

Think tank Prosper Australia has for years demonstrated shocking numbers of vacant dwellings unavailable for rent. A hefty vacancy tax – much greater than the Victorian rate of 1% of property value, while NSW still has none for Australian owners – would lead to many more homes being released onto the market.

The property developers’ argument that we have to build more because that’s the only way to make housing more affordable has been repeatedly refuted by years of careful research.

Tens of thousands of upmarket dwellings have been added to the inner cities of Melbourne and Sydney over the past 20 years, with no reduction in prices across the board. While upmarket unit prices might drop a little when vacancy rates in that submarket increase, their developers are keenly alert to any dip in profits. At the slightest hint of surplus they just stop building.

If housing affordability is the object of urban expansion, let’s grasp that nettle: the only way to achieve it is to build affordable housing, it’s that simple. More than enough land is available within the urban growth boundaries for residential development.

Recent research from Prosper shows there are 84,000 undeveloped housing lots on nine Australian master-planned estates alone. This does not include the many inner-city regeneration projects already under way. Social housing in these areas should be the focus of urban planning before any more land is released.

What about ‘under-developed’ urban lands?

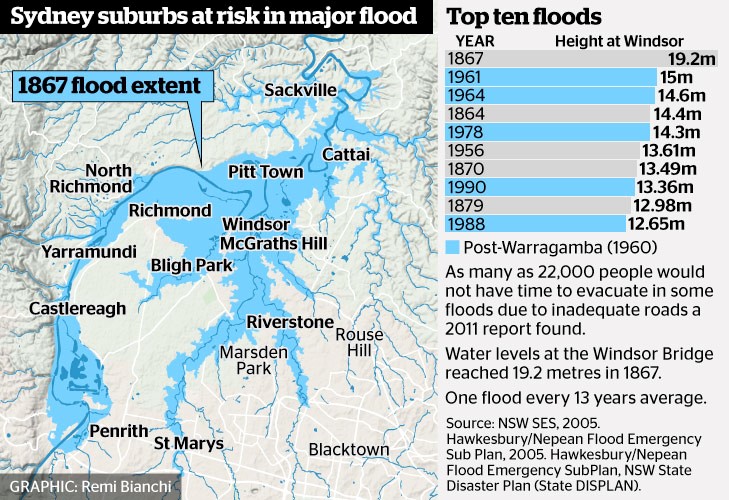

Further expansion of the inner cities of Melbourne and Sydney can only encroach onto low-lying, flood-prone industrial lands that were long ago deemed unsuitable for residential development. It would be folly, or very expensive, to build housing there.

These areas are and still can be used for manufacturing, however, and not just the new niche urban manufacturers that gentrifying councils so love to love. Older industries that are even now being displaced from Fishermans Bend in Melbourne and Blackwattle Bay in Sydney can easily coexist with artisanal bakeries and coffee roasters.

The imperative to promote sustainable local production is stronger than ever now that the pandemic and war have exposed the vulnerabilities of global supply lines. Our diminishing industrial lands really should be kept for industry, until such time as sea-level rise claims them as wetlands.

This is not an argument for decreasing construction activity: there is much work to be done retrofitting existing buildings. These need to be re-clad, better ventilated, opened to passive cooling and adapted to a warming climate.

The ongoing regeneration projects in Melbourne and Sydney need a lot more attention. Docklands, Darling Harbour and Barangaroo could become useful with some serious interventions. The emerging Fishermans Bend and Blackwattle Bay developments have already released more land than their planners know what to do with.

A forward-looking city plan would consolidate and advance what that city already has. That’s the way to build revenue streams that are environmentally, socially and politically sustainable.![]()

Kate Shaw, Honorary Senior Fellow in Urban Geography and Planning, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

NSW State of the Environment report – a mixed result

The EPA released the three-yearly State of the Environment Report (SoE) in February. There are some pluses but mostly it paints a sorry picture. It boils down to the human impact from climate change and population growth.

The Australian SoE was sent to the Minister for the Environment, Susan Ley, in December. But it is has not been made public yet. The minister is required to table the report in parliament within 15 sitting days of receiving it. Parliament has sat only briefly this year so the government is not legally required to release it until the next parliament forms. What is she trying to hide?

For a change the NSW report does acknowledge the significance of population growth ‘population growth is the main driver of environmental issues’.

Yet, the NSW government’s top bureaucrats have urged the premier, Dominic Perrottet, to take a national leadership position and advocate a temporary five-year doubling of the pre-pandemic migration rate, which would increase the NSW population by about 2 million in 5 years. The argument is that this would rebuild the economy and address labour shortages.

The economy seems to be doing all right, thank you! Labour shortages seem to be a perpetual issue despite high immigration for most of this century. Perhaps it is more to do with wages being too low in the affected sectors of the economy. In 2018, Gladys Berejiklian, called for a pause to enable the state’s infrastructure to catch up. This still hasn’t happened.

Some pluses in this SoE report include:

- Air and urban water quality are generally good but the state’s major inland river systems continue to be affected by water extraction, altered river flows, loss of connectivity and catchment changes such as altered land use and vegetation clearing.

- Greenhouse gases are declining having fallen by 17% since 2005. Renewable energy sources have grown but they are still only 19% of electricity power in 2020. But, unlike the federal government, there is actually a plan to get to net zero by 2050.

- About 9.6% of NSW is conserved in the public reserve system. The rate of new reservations has increased markedly, with around 305,000 ha being added to reserves since 2018.

What about biodiversity?

The story on biodiversity is very different. Much loss can be attributed to the Black Summer bushfires but the downward trend has accelerated due to climate change and land clearing.

Improvements have been made through the Saving our Species program. $175 million has been allocated to the program for the 10 years to 2026, and $240 million has been allocated over five years to support a greater commitment to long-term conservation of biodiversity on private land.

Land clearing is the greatest threat to biodiversity. Land clearing and logging of native forests continue at record levels (54,500 hectares in 2019). Unrealistic logging contracts are driving the rates of tree felling which is crazy when several reports have shown that the government is losing money on logging operations. Land clearing is now so bad that in February the koala was declared an endangered species under the Commonwealth EPBC Act.

Money is going into saving species but the amount of land clearing is likely to be creating more threatened species. Invasive species are also a major threat. The regulatory framework under the Biodiversity Conservation Act is failing as was predicted by environment groups and the EDO.

Population and climate change

This important discussion paper on population and climate change by Ian Lowe, Jane O’Sullivan and Peter Cook was published in February 2022 by Sustainable Population Australia. Here is their summary.

The relationship between population and climate change is complex. At a basic level, for a given lifestyle (consumption pattern), emissions of the greenhouse gases that cause climate change are directly proportional to the size of the population. For example, if Australia’s recent population growth rate of about 1.5% per year were to continue, in less than 50 years we would double our demands for energy, food, water and all natural resources. All else being equal, we would double our carbon footprint also. On the other hand, in a hypothetical world where we achieve lifestyles entirely free from greenhouse gas generation, how many of us there were would make no difference to the climate. But even if this were achievable, which is questionable, we could decarbonise our lifestyles more rapidly if population growth was not constantly adding to the demand for energy and resources. Hence, the rate of population growth will make a considerable difference to the cumulative emissions generated during the transition. Furthermore, population growth greatly increases our vulnerability to the impacts of climate change.

The population issue has had a controversial history which has led to the development of a ‘taboo’ against talking about population as a policy-relevant factor. This paper calls for a new level of maturity in discussing the population issue. It should no longer be acceptable for unfounded accusations of racism to be used to silence respectful and thoughtful discussions about population growth. It should no longer be acceptable – at an epochal moment of existential risk for human civilisation – for climate policy prescriptions to conspicuously exclude population-related actions in the face of abundant evidence (as reported in this paper) that such measures are feasible, effective and consistent with human rights and democratic values. Ending global population growth more swiftly and at a lower peak is a necessary but not sufficient condition for overcoming the climate crisis.

Population and consumption work together

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says:

Globally, economic and population growth continue to be the most important drivers of increases in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion.

But these are not independent contributors to emissions; they multiply each other. Most emissions are attributable to the richest billion people, but their economic growth since 1970 has not increased their average emissions per person. The growth in emissions has come from lifting multitudes of poor people to a modest middle-class lifestyle in places like China and India.

It is futile to ‘blame’ past emissions on either population or consumption patterns when they are the product of both. What should be of more interest to us is the extent to which the future challenges of climate change, including emissions reduction and adaptation, can be lessened by giving due attention to population growth. This paper argues that our climate change response can’t afford to ignore the potential to minimise further population growth.

Slow-response actions are no less urgent

Nobody expects addressing population growth alone to solve climate change. There is no intention to deflect attention from high- emissions consumption patterns, nor to blame the poor for the excesses of the rich. Demographic inertia means that even concerted efforts to slow population growth are unlikely to have significant impact on the timescale demanded by the climate crisis. Measures to decarbonise our energy system and reverse the loss of vegetation and biodiversity are needed urgently in this decade, if we are to avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change. Measures to reduce childbirth will take decades to make an appreciable difference to greenhouse gas emissions and human demands on nature.

Nevertheless, how well we do in the second half of this century will depend more on what we do about population growth this decade than on any actions that will remain available to us in 2050. If the successful efforts to promote voluntary family planning adoption in the 1970s and ’80s had not been abandoned in the 1990s, the global population might now be on track to peak below 9 billion. Because of decisions made in the 1990s, we’re heading for 11 billion or more. But if we renew family planning efforts now, a peak below 10 billion is possible and we could end this century with fewer than 8 billion people. If we wait until 2050, 11+ billion would be locked in.

A slow fruition does not make population action any less urgent. As the proverb says, ‘The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.’ So it is with addressing global population. The climate crisis is largely a product of the short- sightedness of political responses decades ago. Those who say that reducing birth rates is too slow to be relevant to the climate change response are suffering the same short-sightedness that created the problem they seek to fix.

In rich countries, fewer people means lower emissions and fewer vulnerabilities

Any increase of population in the more affluent countries will add to those countries’ use of resources and their greenhouse gas emissions. In a rich country, having fewer children does more to slow climate change than any of the other actions often advocated, such as eating less meat, avoiding air travel or using only renewable energy. If immigration is high enough to cause population growth, it also increases a country’s emissions, but some people argue that it makes no difference globally. This is untrue: the average migrant to Australia increases their carbon footprint fourfold by adopting Australian lifestyles. While Australians have recently reduced their per capita emissions a little, Australia’s total emissions from energy have risen 49% since 1990 due entirely to population growth of 8.3 million people.

Australia is not only one of the world’s largest per capita emitters of greenhouse gases, it is also among the countries likely to be most affected, in terms of negative impacts on agriculture, water supply, bushfire threat and extreme weather events. All these threats are intensified by the threat-multiplier of population growth.

The current Australian government policy of encouraging high levels of migration could see the 2060 population approaching 40 million and continuing to grow rapidly. That scale of increase would significantly magnify the task of producing enough clean energy to meet our material needs within a responsible carbon budget. Australian agriculture is unlikely to feed that number during increasingly frequent and severe droughts, and water security will depend on costly and energy-intensive desalination or recycling. These serious vulnerabilities are entirely avoidable if we choose population stabilisation.

In poor countries, smaller families are essential for adaptation

Population growth heightens vulnerability to climate change to a much greater extent in poor, high-fertility countries. For most of these countries, population growth itself is a greater threat to security and wellbeing than climate change is. Saying this does not in any way diminish the serious impacts of climate change. However, if a projected 11–25% reduction in crop yields this century due to climate change is considered a crisis, it is absurd to claim, as many people do, that population growth in high-fertility countries is not important when it will diminish the available water and agricultural land per person by a factor of three or more, while ensuring high levels of unemployment and poor infrastructure provision. While family size should be considered part of emissions reduction efforts in rich countries, it should be integral to adaptation efforts in poor countries. Nevertheless, the emissions caused by growing numbers of the poor are not insignificant. Deforestation is particularly vulnerable to population pressure.

Currently, family planning services are badly underfunded, denying many women access to safe and reliable contraception. As a result, the fall in birth rates has been much slower than was anticipated a generation ago, unemployment is rampant and hunger is once more on the rise.

Many of the beneficial impacts of lower birth rates are enjoyed much more rapidly than their effect on carbon emissions. These benefits include greater autonomy of women, health of infants, food security of families, protection of biodiversity, employment prospects for youth and economic development of nations. If climate adaptation is dominating the agenda for international aid, it makes sense that family planning should be included as an adaptation measure.

Climate change will affect world population

The other side of the coin is the impact climate change is projected to have on population, through greater loss of life. The frequency of extreme heat events, floods and crop-destroying droughts is projected to increase substantially. Some Pacific islands and low-lying coastal areas will become uninhabitable, causing either loss of life or relocation of whole populations. Mass migrations could possibly in turn lead to conflict between the displaced people and those whose traditional lands they enter. However, responses to climate change can have some beneficial health impacts. Urban air pollution and indoor smoke exposure are both major causes of premature deaths, and might be substantially reduced by electrification of energy systems. It is difficult to anticipate the net effect on population trends.

Only low-population scenarios can keep warming below 2°C

The most compelling reason to include population in the climate change response is that climate mitigation models are only able to achieve sufficient emissions reduction if their scenarios assume a rapid peak and decline in global population. These assumptions are not readily visible: they are hidden under the labelling of scenarios such as ‘SSP1’ or ‘SSP2’. Without making these assumptions explicit, and discussing the actions that could help achieve the required birth reductions in a way that elevates people’s rights and freedoms, these scenarios can’t become reality.

Addressing population growth alone can’t solve climate change, but not addressing it will ensure we fail.

Feeling adrift in a sea of false hope

A couple of months ago, I sat in on an Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) event via Zoom for its donors and supporters that promoted its latest climate change campaign. As a long-serving councillor and former vice president of ACF, I was interested to hear about their campaign plans, which they explained are based on a poll of 15,000 people who indicated a desire for firm action on climate change. However, at the end of it, I felt isolated and alone. I felt I had moved on in my thinking, while ACF has not.

The presentations by senior ACF staff were earnest and uplifting and the comments posted in response were enthusiastic and supportive. But I felt myself estranged from the event. I found myself recalling how often, over my 30 years of enthusiastic involvement with ACF, I had felt uplifted and inspired by the same style of presentations by ACF’s key personnel. Now, not so and it felt a bit like having lost a faith.

So, what has changed for me as ACF barrels along in its customary manner? It comes down to a realisation that ACF, and environmentalism more generally, is stuck with talking about the symptoms of the environmental crisis, while ignoring the underlying causes. It is also locked into a largely fruitless campaign mode that is focused on targeting marginal seats in each Federal election. This has been its style since I joined its council in the 1980s and it remains a deeply entrenched, culturally embedded modus operandi.

The ACF people are intelligent, well-meant and deeply committed environmentalists, and for that they have my great respect. But they, and seemingly their supporters and donors who joined in this event, now appear to me to be tunnel-visioned and misguided in their fervour. First, and foremost, there is the assumption that climate change is the major existential threat that ACF and the wider environmental movement must address. It is their highest priority. And second, there is the additional assumption that this threat can be averted through a political campaign focussed on key marginal seats that will somehow bring about a radically different response. I hear myself thinking, ‘same old, same old’, looking back over forty years of ACF campaigning strategy. When will the penny drop that this is a fruitless strategy?

I could have submitted a comment to the event along the following lines:

When will ACF connect its climate change and biodiversity work to a deeper sustainability agenda that encompasses population growth, consumption, economic growth and technology – the underlying drivers of imminent collapse?

That would have been a real ‘party pooper’ contribution that I am sure would not have been welcomed by the ACF organisers on the night. It probably also would have been dismissed as inappropriate or irrelevant by most of the supporters and donors participating in the event.

The reality is that these deeper and more complex issues have been either ignored or dismissed by most ACF staff for much of its existence. This is despite the efforts of a number of its elected councillors and former Presidents over many years (ranging from Sir Garfield Barwick in the early 1970s to Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe more recently), to draw attention to them. The focus within ACF staff remains on an agenda dominated by the twin environmental pillars of climate change and biodiversity. But it would be unfair to level this criticism only at ACF. The environmental movement more generally, both here in Australia and in most other Western countries overseas, has largely displayed the same myopia in framing their campaigning and advocacy efforts.

As to the reasons for this behaviour, a fellow ex-ACF councillor, Jonathan Miller, offered me recently the following salient observations:

- The internal perception that it is easier to attract public support for issues such as climate change and biodiversity than for complex and less tangible issues such as population growth, consumption and economic growth.

- The additional perception that tackling the drivers of unsustainability is more difficult conceptually, much harder to win in the long-term and that it is more difficult to identify ‘wins’ to supporters and members.

- A shift in the profile of ACF (and other ENGO organisation) activists and their collective culture from those who deeply understand and love the bush (e.g. bushwalkers and those with natural science degrees) to those with broader social issue concerns (and whom, in turn, are particularly reluctant to tackle issues such as immigration-driven population growth in Australia).

Reinforcing the first of these points, the US founder of the Post Carbon Institute, Richard Heinberg, has offered the following observation about environmentalists more generally in a recent blog (The Only Long-Range Solution to Climate Change, Museletter #343 September 2021):

It’s understandable why most environmentalists frame global warming the way they do (by targeting the fossil fuel industry). It makes solutions seem easier to achieve. But if we’re just soothing ourselves while failing to actually stave off disaster, or even to understand our problems, what’s the point?

This succinctly echoes exactly where my own thoughts have arrived at after over 40 years of involvement with environmental law and environmentalism. I have come to believe that:

- climate change is essentially a symptom (admittedly a very powerful one) of an underlying ‘growth’ disease; and

- that the current political system, which is the hand maiden of capitalism and completely in its capture, is incapable of producing an effective response to climate change, much less the deeper challenge of avoiding ecological collapse and transitioning to sustainability.

On the latter score, the efforts by ACF and other ENGO’s to scramble for the crumbs falling from the table at each, successive federal election, seem both flawed and largely fruitless. Over the years, even though ACF does not directly support any political party, it has often engaged in targeting marginal seats where the ALP may have a chance of defeating the Coalition. The relationship with the Australian Greens has remained strained. And, after watching on ABC TV this week the first episode of the series, Big Deal, which laid bare the lack of any safeguards with respect to corporate political donations, it is clear where the most powerful influences on federal politics come from.

So, this is why I am left feeling alone and isolated. Where are the voices to raise the larger sustainability agenda? What is the point of environmentalism, however well-intentioned, if it proceeds in almost deliberate disregard of this larger agenda? How can this agenda be pursued when those most likely to support it do not, or are not willing to, recognise it? And what is the point of trying to engage with the current, corrupt political system in which a large proportion of Australian citizens have lost all confidence?

My response to these questions, perhaps surprisingly, remains hopeful. There are many voices emerging globally in support of a deeper sustainability agenda, including some luminaries in Australia. Environmentalism has been a meritorious movement over the past fifty years but it now must be seen as one that is limited in its vision and incapable of promoting a deeper sustainability agenda. This agenda must and will emerge from other sources and directions. And the goal must be to promote this agenda through radical social, economic and political reforms – these will be the pathways of the transition to a sustainable future that embodies ecological resilience and a human civilisation that is living within its means.

To develop these ideas further, I am engaged currently in writing a book entitled The Great Transition: From the Anthropocene to the Ecolocene which I hope to get published in about eighteen months from now.

This article is reproduced with permission. It was published in the Sustainable Population Australia newsletter, issue #145, November 2021. It was written by Rob Fowler, Adjunct Professor at the School of Law, University of Adelaide. He was a vice-president of the ACF from 2008 to 2015.

They are all Fiddling while the World Burns

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

Part of that mobilisation will surely be the recognition that population growth is a major cause of ongoing warming. Halve the population and we roughly halve much of the pollution causing warming as well as other pollution such as plastics.

That brings us to what’s happening in Australia.

With an average of about 12.5 million people over the past 220 years we have degraded our major river systems, caused a terrible list of plant and animal extinctions, degraded our topsoils and more and are now busily overpopulating our major cities - with consequent physical and social consequences.

Our current annual rate of population growth of 1.7% will lead to doubling every 42.5 years. That means 50 million in 2061, 100 million in 2104 and 200 million in 2146 and so on.

You would think that those numbers would be enough to promote some discussion of where we are heading and where we want to head and how to go about it. But no, the Coalition, Labor and the Greens, along with our major environmental groups such as the ACF and NCC, all seem intent on ignoring the elephant and ensuring further degradation and destruction of the Australian natural world.

Why is this thus? We think there are a few reasons.

Firstly there is huge ignorance around the maths of exponential growth. It’s amazing to find so many educated, even scientifically educated, people who have not a clue about the consequences of 1.7% growth.

Secondly, the mainstream media and political world has insisted in conflating population growth with protecting the borders and racism. You talk about less population and so many assume that you are dog-whistling and really mean that we don’t want those refugees. The ABC has a terrible record in this regard.

Thirdly, the big end of town, those whose lobbyists haunt the corridors of our parliaments, cheque books in hand, has convinced many that without economic growth we shall all become destitute. That is simply self-serving rubbish that suits their economic interests. More people mean more housing, more furnishings, and more of most things. It’s not the environment they worry about – it’s their never-ending need for more economic activity and more profit.

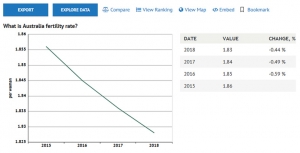

Australia’s fertility is now about 1.83 which will eventually produce a declining population because it is below the replacement level of 2.1. In addition, some 50,000 people leave Australia permanently every year. This means that we can accept 70,000 immigrants per year and eventually stabilise our population. We should do so. There is plenty of room there for refugees.

STEP has never dog-whistled!

It’s hard, however, to know how we shall ever start to manage the situation so long as none of the elites are prepared to discuss it and so long as the environmental organisations don’t have the guts to confront it.

We have been writing about population for over thirty years and much more detail can be gleaned from our Position Paper on Population.

By John Burke, former president of STEP and chief author of STEP’s Position Paper on Population, has written this update on the population issue.

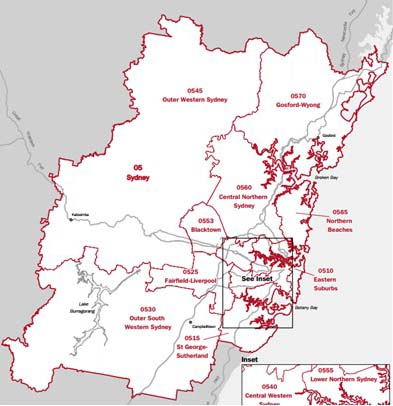

City Populations

There has been much media interest in the report that Sydney's population has reached 5 million. What has also been reported is that Melbourne’s population is growing faster than Sydney’s and may soon exceed it.

Sydney

The problem I have with this is that Sydney includes the Central Coast and the Blue Mountains, but not Wollongong. I don't advocate including Wollongong but leaving out the other two plus the Wollondilly Shire (Picton) we have 5.25 – 0.33 – 0.08 – 0.05 = 4.79 million. We could go further and leave out the farther reaches of Hornsby, Baulkham Hills and other local government areas.

Melbourne

Melbourne includes the Mornington Peninsular (0.16 million) which is debatable. Other areas should also be removed (allow 0.05 million). So, 4.67 – 0.16 – 0.05 = 4.46 million which is 93% of Sydney’s population.

Distortions

Part of the problem for the Australian Bureau of Statistics is that the outer suburban local government areas cover large areas of peripheral rural land. The Sydney map at a guess is at least 75% rural and this leads to massive distortions when people try to compare densities.

This data below (from Population Australia) is rubbish. Population Australia is a website specialising in research for Australia population growth trends and estimation. It is not clear who is behind this group but the data seems to be coming from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

More on this some other time.

Position | City | Population density |

1 | Melbourne | 453/km2 |

2 | Adelaide | 404.205/km2 |

3 | Sydney | 400/km2 |

4 | Perth | 317.736/km2 |

5 | Canberra | 173.3/km² |

6 | Brisbane | 145/km2 |

7 | Hobart | 124.8/km2 |

8 | Darwin | 44.976/km2 |

Jim Wells has been delving into published statistics that are more than meets to eye.

The Decoupling Delusion: Rethinking Growth and Sustainability

Our economy and society ultimately depend on natural resources: land, water, material (such as metals) and energy. But some scientists have recognised that there are hard limits to the amount of these resources we can use. It is our consumption of these resources that is behind environmental problems such as extinction, pollution and climate change.

Even supposedly 'green' technologies such as renewable energy require materials, land and solar exposure, and cannot grow indefinitely on this (or any) planet.

Most economic policy around the world is driven by the goal of maximising economic growth (or increase in gross domestic product – GDP). Economic growth usually means using more resources. So if we can’t keep using more and more resources, what does this mean for growth?

Most conventional economists and policymakers now endorse the idea that growth can be 'decoupled' from environmental impacts – that the economy can grow, without using more resources and exacerbating environmental problems.

Even the then US president, Barack Obama, in a recent piece in Science argued that the US economy could continue growing without increasing carbon emissions thanks to the rollout of renewable energy.

But there are many problems with this idea. In a recent conference of the Australia-New Zealand Society for Ecological Economics (ANZSEE), we looked at why decoupling may be a delusion.

The Decoupling Delusion

Given that there are hard limits to the amount of resources we can use, genuine decoupling would be the only thing that could allow GDP to grow indefinitely.

Drawing on evidence from the 600-page Economic Report to the President, Obama referred to trends during the course of his presidency showing that the economy grew by more than 10% despite a 9.5% fall in carbon dioxide emissions from the energy sector. In his words:

…this 'decoupling' of energy sector emissions and economic growth should put to rest the argument that combating climate change requires accepting lower growth or a lower standard of living.

Others have pointed out similar trends, including the International Energy Agency which last year – albeit on the basis of just two years of data – argued that global carbon emissions have decoupled from economic growth.

But we would argue that what people are observing (and labelling) as decoupling is only partly due to genuine efficiency gains. The rest is a combination of three illusory effects: substitution, financialisation and cost-shifting.

Substituting the Problem

Here’s an example of substitution of energy resources. In the past, the world evidently decoupled GDP growth from buildup of horse manure in city streets, by substituting other forms of transport for horses. We’ve also decoupled our economy from whale oil, by substituting it with fossil fuels. And we can substitute fossil fuels with renewable energy.

These changes result in 'partial' decoupling – that is, decoupling from specific environmental impacts (manure, whales, carbon emissions). But substituting carbon-intensive energy with cleaner, or even carbon-neutral, energy does not free our economies of their dependence on finite resources.

Let’s get something straight: Obama’s efforts to support clean energy are commendable. We can – and must – envisage a future powered by 100% renewable energy, which may help break the link between economic activity and climate change. This is especially important now that President Donald Trump threatens to undo even some of these partial successes.

But if you think we have limitless solar energy to fuel limitless clean, green growth, think again. For GDP to keep growing we would need ever-increasing numbers of wind turbines, solar farms, geothermal wells, bioenergy plantations and so on – all requiring ever-increasing amounts of material and land.

Nor is efficiency (getting more economic activity out of each unit of energy and materials) the answer to endless growth. As some of us pointed out in a recent paper, efficiency gains could prolong economic growth and may even look like decoupling (for a while), but we will inevitably reach limits.

Moving Money

The economy can also appear to grow without using more resources, through growth in financial activities such as currency trading, credit default swaps and mortgage-backed securities. Such activities don’t consume much in the way of resources, but make up an increasing fraction of GDP.

So if GDP is growing, but this growth is increasingly driven by a ballooning finance sector, that would give the appearance of decoupling.

Meanwhile most people aren’t actually getting any more bang for their buck, as most of the wealth remains in the hands of the few. It’s ephemeral growth at best: ready to burst at the next crisis.

Shifting the Cost onto Poorer Nations

The third way to create the illusion of decoupling is to move resource-intensive modes of production away from the point of consumption. For instance, many goods consumed in Western nations are made in developing nations.

Consuming those goods boosts GDP in the consuming country, but the environmental impact takes place elsewhere (often in a developing economy where it may not even be measured).

In their 2012 paper, Thomas Wiedmann and co-authors comprehensively analysed domestic and imported materials for 186 countries. They showed that rich nations have appeared to decouple their GDP from domestic raw material consumption, but as soon as imported materials are included they observe 'no improvements in resource productivity at all'. None at all.

From Treating Symptoms to Finding a Cure

One reason why decoupling GDP and its growth from environmental degradation may be harder than conventionally thought is that this development model (growth of GDP) associates value with systematic exploitation of natural systems and also society. As an example, felling and selling old-growth forests increases GDP far more than protecting or replanting them.

Defensive consumption – that is, buying goods and services (such as bottled water, security fences, or private insurance) to protect oneself against environmental degradation and social conflict – is also a crucial contributor to GDP.

Rather than fighting and exploiting the environment, we need to recognise alternative measures of progress. In reality, there is no conflict between human progress and environmental sustainability; well-being is directly and positively connected with a healthy environment.

Many other factors that are not captured by GDP affect well-being. These include the distribution of wealth and income, the health of the global and regional ecosystems (including the climate), the quality of trust and social interactions at multiple scales, the value of parenting, household work and volunteer work. We therefore need to measure human progress by indicators other than just GDP and its growth rate.

![]() The decoupling delusion simply props up GDP growth as an outdated measure of well-being. Instead, we need to recouple the goals of human progress and a healthy environment for a sustainable future.

The decoupling delusion simply props up GDP growth as an outdated measure of well-being. Instead, we need to recouple the goals of human progress and a healthy environment for a sustainable future.

James Ward, Lecturer in Water & Environmental Engineering, University of South Australia; Keri Chiveralls, Discipine Leader Permaculture Design and Sustainability, CQUniversity Australia; Lorenzo Fioramonti, Full Professor of Political Economy, University of Pretoria; Paul Sutton, Professor Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Denver, and Robert Costanza, Professor and Chair in Public Policy at Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Greater Sydney Strategy

It's important that as many people as possible comment on the Greater Sydney Strategy and the North District Plan by 31 March 2017.

Towards Our Greater Sydney 2056 is a 40 year vision that spells out the anticipated rate of growth and framework for employment and population distribution. How this is done will ultimately determine the long-term impacts on our natural areas, STEP’s chief focus.

For a city the size of Sydney, strategic planning over a 40 year period is important. However as outlined below there are matters of serious concern.

High Rate of Growth

On p8 there is this statement:

Greater Sydney is experiencing a step change in its growth with natural increases (that is an increase in the number of births) a major contributor. We need to recognise that the current and significant levels of growth, and the forecast higher rates of growth are the new norm rather than a one-off peak or boom.

Given the clear impacts of high growth rates on our urban amenity this statement needs closer scrutiny.

Refer to the table below for the projected growth rates and the figure below for the net overseas migration component.

| Region | Population 2011 | Projected population | ||

| 2036 | Change 2011–36 | % change 2011–36 | ||

| Greater Sydney | 4,286,350 | 6,421,950 | 2,135,650 | 49.8% |

| Rest of NSW | 2,932,200 | 3,503,600 | 571,400 | 19.5% |

From the figures the total projected increase in population in NSW from 2011–36 is around 2.7 million. Of this, for the same period, the total from net overseas migration is around 1.7 million, leaving the natural growth at around 1 million.

A recent report by the Planning Institute of Australia on population trends, Through the Lens: Megatrends Shaping our Future (p12) concluded:

Overseas migration continues to be the biggest contributor to population growth.

Net overseas migration for Australia since 1976 is shown in the lower figure. On p12 it says that:

Of the three basic factors determining population growth (fertility/births, mortality/deaths and migration) the net migration rate is most subject to policy intervention, and thus the most uncertain in future projections.

Since the net migration rate is the primary determinant of Australia’s population growth and is controlled by government policy, it is clearly possible to regulate the overall population growth rates of Australia to ensure they are at acceptable levels and anticipated benefits are broadly realised.

Since the net migration rate is the primary determinant of Australia’s population growth and is controlled by government policy, it is clearly possible to regulate the overall population growth rates of Australia to ensure they are at acceptable levels and anticipated benefits are broadly realised.

The regulation of inflation by the Reserve Bank has proved beneficial relative to an unregulated economy. Regulation of Australia’s overall population level and age structure through adjustment of net migration targets by a Federal government agency could prove beneficial to planning within Australia. This agency has to work in concert with state governments that bear the brunt of the implementation consequences.

High growth rates are resource intensive, difficult to manage and can lead to significant long-term environmental impacts. In the past these have included a higher proportion of defective buildings, lags in required new infrastructure with traffic congestion increasing and damage to bushland and watercourses from greater urban stormwater run-off.

The current proposed annual growth rates of around 1.6% are too high and need to be reduced to the more manageable levels in the previous three decades of around 1%. The Mercer World’s Most Liveable Cities ranking indicates that beyond a population of around 6 million liveability declines. Sydney has to recognise that growth cannot be infinite and ultimately must plan for a zero net growth future.

The Greater Sydney Commission may not have a say in the growth projections but we think people should be able to express their views through the current consultations process and local federal and state MPs.

Urban Renewal

On p8 it states that the shorter term need for additional new housing capacity is greatest in the North and Central Districts. While this will lead to more high-rise development along the railway line it is important that urban conservation corridors are retained.

For example it is possible to walk from Gordon, Killara and Roseville Stations through high quality urban conservation areas to the bushland that leads to Garigal National Park. The value of these conservation corridor links from railway stations to our national parks can only increase with time.

Medium Density Infill Development

On p9 it states:

Many parts of suburban Greater Sydney that are not within walking distance of regional transport (rail, light rail and regional bus routes) contain older housing stock. These areas present local opportunities to renew older housing with medium density housing. Medium density housing is ideally located in transition areas between urban renewal precincts and existing suburbs, particularly around local centres and within the 1 to 5 km catchment of regional transport.

A 1 to 5 km catchment from the railway stations and regional bus routes would include virtually all of the North Shore. Future medium density in these areas is likely to be fast-tracked by developers using the NSW government’s proposed Complying Medium Density Housing Code (CMDHC).

Provided prescribed standards are met this could allow building density increases by as much as a factor of two without the need for consent. Because of its indiscriminate nature, for those areas impacted by the code, it could lead to increases in dwelling numbers significantly in excess of those planned for.

The CMDHC is proposed in extensive single dwelling R2 zones for those councils where multi-dwelling housing or dual occupancy is permissible in this zone. If one council allows multiple dwellings it will flow through to all the original member councils when they amalgamate.

Examination of the relevant LEPs indicates all the amalgamated councils in the North District will be impacted with the exception of Hornsby–Ku-ring-gai. STEP strongly opposes application of CDMH in any residential zone other than the medium density R3 zone.

Economic Priorities

On p7 there is a focus on the economic growth from inbound tourism. This would be a serious concern if our bushland and national parks are treated as assets for commercialisation. Sensitive natural bushland areas can easily be damaged from overuse and need protection. Private leasehold of areas with existing bushland and clearance for accommodation should not be supported.