Displaying items by tag: population debate

Population – big Australia back on the agenda

The Centre for Population, part of federal Treasury, was established in 2019 to improve data collection on how Australia’s population is changing and the implications of these changes.

The Centre makes an annual statement of population including analysis of changes over the past year. The 2022 statement has recently been released. This report also covers projections of future population levels out to 2033 as well as analysis of the impact of COVID on recent migration and mortality experience. It is good to see regular information in one location instead of previously having to delve into ABS and Department of Immigration website data.

This report brought out the usual hype in the media about the need for new migrants to stave off the ageing population burden and labour skill shortages. There is only limited discussion of the impact the growth will have on significant aspects of social and environmental wellbeing, such as cost of housing and biodiversity.

Projections for next 10 years

The baseline assumption of future net overseas migration (NOM) is 235,000 per annum based on the average over recent years prior to the COVID-19 slowdowns plus some adjustment for policies increasing permanent placements. Despite the COVID experience we are still trying to catch up on the demand for services and infrastructure that was generated by the escalation of growth that was started by the Howard government in 2006 and has been perpetuated by subsequent Labor and Coalition governments ever since. Prior to 2006 NOM was half that level or less.

Our current population is 26.1 million (as at September 2022). The projection in the Population Statement 2022 is that we will reach 30 million by mid-2033. However, the level of migration has been ramped up since the Labor government came to power as a backlog of applications is being processed and international students are flooding back. It is estimated that the NOM for the next two years will be 650,000 so that growth including natural increase (births less deaths) will approach 950,000. No wonder there is a housing crisis! The slowdown during the COVID-19 shutdown is becoming irrelevant.

Intergenerational report — projections to 2060

The 2021 Intergenerational Report provides longer term projections of the outlook for the economy and budget.

This report used the same assumption for NOM of 235,000 pa for the whole 40 years of their projections. The total population in 40 years’ time is projected to be an eye-watering 39 million. That is a 13 million more people, a 50% increase! The growth over the past 40 years was 11 million. We can see the impact of that number. To use the hackneyed catch phrase, it is unsustainable. Liveability of our cities has declined. The State of the Environment Report 2021 showed significant declines in biodiversity. Surveys have highlighted that citizens do not want this high rate of growth to continue.

The governments at state and federal level express plans to stop species extinctions, reduce carbon emissions and improve liveability but they carry on, regardless of popular opinion, doing nothing to stop the forces that go against these policies; vegetation clearing, bigger houses, more roads.

Apparently, there is no contemplation that our growth will ever slow down. The concept of longer term planning whereby the growth can be reduced over time is anathema to the politicians and business even though it would be welcomed by voters. We have to accept the reality of adapting by increasing skill levels, retraining the existing workforce and increasing workforce participation into retirement age. The easy option is still being taken by importing skills from countries that need them more. The hard decisions are being left to future generations.

Alternative viewpoints

Sustainable Population Australia, an environmental advocacy organisation, has recently published some discussion papers with academic analysis calling into question the status quo.

The housing crisis is a population growth crisis

Some of the key points made are:

- The connection between population growth – driven by high immigration – and high housing cost inflation is often ignored or denied in political circles but is accepted as an undeniable fact by almost everyone knowledgeable about the property industry.

- An accumulation of ill-advised policy measures (e.g. negative gearing, reduction in capital gains tax and first home buyer grants) have combined with accelerated population growth to create a perfect housing storm.

- A lower net migration level is needed to slow growth and stabilise population size. Even an optimally regulated market will not prevent housing inflation in the face of endless population growth.

- Lower, well-targeted immigration will not cause intractable skills shortages or unmanageable population ageing, but will reduce housing stress and inequality, and improve environmental amenity.

How many Australians? The need for Earth-centric ethics

This discussion paper has been written by Dr Paul Collins, an historian, broadcaster and the author of 17 books on Catholicism, the papacy, environmental ethics and population issues.

The paper addresses the competing demands of human beings seeking a better life with the rights of our natural systems to prevail against the demands of human activities.

Despite its physical size, Australia is limited in biophysical and geophysical terms. All our State of Environment reports have found the demands of the current population have been degrading natural systems irreversibly. We are not living sustainably with the numbers we have at current standards of living.

Millions want to come and share the riches we enjoy. Do we have a moral duty to let them come and allow them a better life? Or should we protect the ecosystems in our care?

He calls for a totally new moral principle to guide and govern our ethical behaviour as a species. He argues that we must shift our ethics away from anthropocentrism and economism which pays no heed to our dependence on the natural world. Instead, moral decision-making must give priority to the Earth, biodiversity, climate stability and the integrity of natural systems.

The case for degrowth: Stop the endless expansion and work with what our cities already have

Australian cities are good at growing – for decades their states have relied on it. The need to house more people is used to justify expansion out and up, but it is the rates, taxes and duties that flow from land transfers and construction that drive the endless development of Melbourne and Sydney in particular. Property development is the single largest contributor to Victorian and New South Wales government revenues.

For example, the City of Melbourne’s draft spatial plan proposes new suburbs to the west and north. It’s continuing on a course mapped out in the post-recession 1990s, when Australian governments focused on building on or digging up our great expanses. The plan neither questions the rationale for growth nor, apparently, the deeper effects of the pandemic.

The city council is understandably anxious to attract people back to the centre. The city plan presumes a return to Australia’s high population growth of the 2000s. Expectations of a renewed influx of students, workers and tourists from overseas are based more on hope, however, than reason.

The drivers of population growth are more uncertain and we can no longer depend on global mobility at pre-pandemic levels. Birth rates are falling across the developed world, online international education is improving, and research suggests pandemics will persist while cities encroach on the habitats of so many other species.

Meanwhile, the towers thrown up in the heady years of growth are half-empty and cracking, poorly ventilated, reliant on central air conditioning and not built for more extreme weather or low energy consumption. Melbourne and Sydney’s showcase regeneration projects at Docklands and Barangaroo are more dismal and deserted than ever.

Better needn’t mean bigger

Now is not the time for anyone to announce that their city will become “bigger and better”. Cities don’t have to get bigger to evolve, and sooner or later all will have to reckon with the concept of degrowth.

Australia must become less reliant on imports of skilled workers, students, tourists and materials. We can make better use of local resources and produce much more of what we need here.

Australian cities have very good bones. They have amazing cultural scenes. Their biomedical capabilities are among the world’s best. Our education sector remains eminently exportable online and via existing overseas campuses. The manufacturing sector still has a base to build on and provide many more of the products Australians need. And our renewable energy capacity is unlimited.

We can support our local hospitality and cultural venues better, and increase intercity and interstate patronage. We can invest in research and development and maintain wealth through innovation and production, rather than the eternal consumption of land.

Rethink what we build and why

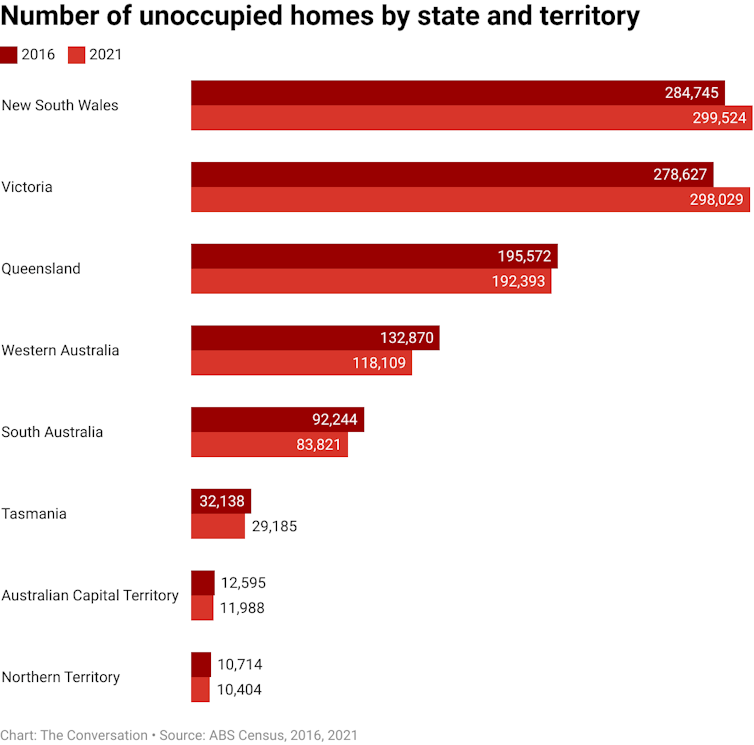

Adapting to global environmental conditions means rethinking not just what and how we build, but why. Before designating land for yet more housing estates, for example, let’s consider that a million homes – 10% of Australia’s housing stock – were empty on census night last year. Nearly 600,000 were in Victoria and New South Wales.

Think tank Prosper Australia has for years demonstrated shocking numbers of vacant dwellings unavailable for rent. A hefty vacancy tax – much greater than the Victorian rate of 1% of property value, while NSW still has none for Australian owners – would lead to many more homes being released onto the market.

The property developers’ argument that we have to build more because that’s the only way to make housing more affordable has been repeatedly refuted by years of careful research.

Tens of thousands of upmarket dwellings have been added to the inner cities of Melbourne and Sydney over the past 20 years, with no reduction in prices across the board. While upmarket unit prices might drop a little when vacancy rates in that submarket increase, their developers are keenly alert to any dip in profits. At the slightest hint of surplus they just stop building.

If housing affordability is the object of urban expansion, let’s grasp that nettle: the only way to achieve it is to build affordable housing, it’s that simple. More than enough land is available within the urban growth boundaries for residential development.

Recent research from Prosper shows there are 84,000 undeveloped housing lots on nine Australian master-planned estates alone. This does not include the many inner-city regeneration projects already under way. Social housing in these areas should be the focus of urban planning before any more land is released.

What about ‘under-developed’ urban lands?

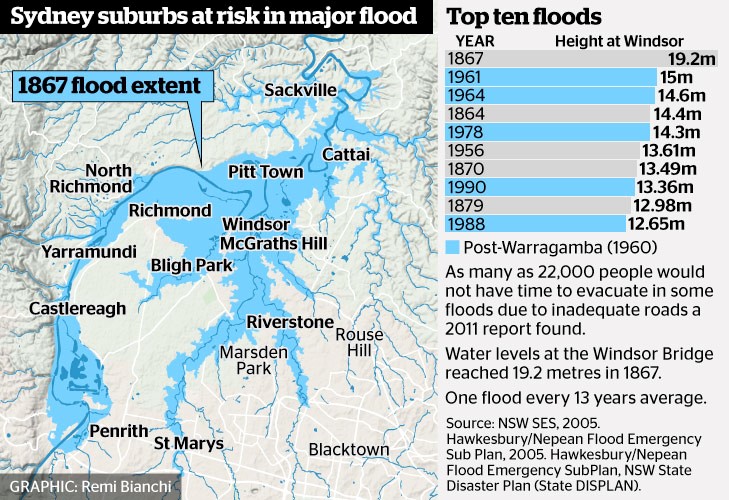

Further expansion of the inner cities of Melbourne and Sydney can only encroach onto low-lying, flood-prone industrial lands that were long ago deemed unsuitable for residential development. It would be folly, or very expensive, to build housing there.

These areas are and still can be used for manufacturing, however, and not just the new niche urban manufacturers that gentrifying councils so love to love. Older industries that are even now being displaced from Fishermans Bend in Melbourne and Blackwattle Bay in Sydney can easily coexist with artisanal bakeries and coffee roasters.

The imperative to promote sustainable local production is stronger than ever now that the pandemic and war have exposed the vulnerabilities of global supply lines. Our diminishing industrial lands really should be kept for industry, until such time as sea-level rise claims them as wetlands.

This is not an argument for decreasing construction activity: there is much work to be done retrofitting existing buildings. These need to be re-clad, better ventilated, opened to passive cooling and adapted to a warming climate.

The ongoing regeneration projects in Melbourne and Sydney need a lot more attention. Docklands, Darling Harbour and Barangaroo could become useful with some serious interventions. The emerging Fishermans Bend and Blackwattle Bay developments have already released more land than their planners know what to do with.

A forward-looking city plan would consolidate and advance what that city already has. That’s the way to build revenue streams that are environmentally, socially and politically sustainable.![]()

Kate Shaw, Honorary Senior Fellow in Urban Geography and Planning, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Infrastructure Cannot Catch Up with Current Population Growth

The state and federal governments are unwilling to discuss the issue of Australia’s population growth. The general view is that the greater the growth the more we will all benefit. Of course their only interest is the simple notion of economic growth, not social wellbeing or environmental quality. Actually economic growth has not been great either. The fact that economic growth per capita has not kept up with inflation has been conveniently ignored.

Australia’s population grew by an average of 400,000 over each of the last five years to reach 25.4 million at 30 June 2019. 60% of this growth is from net overseas migration. This is adding another Canberra every year. The prospect that our population could reach 60 million by the end of the century doesn’t seem to worry the politicians. They appear to believe that this is a fact of life.

Sustainable Population Australia commissioned a report on the infrastructure needs of Australia following the increase in our growth rate this century. The report by Leith van Onselen from business analysis firm Macrobusiness found that unless Australia's population growth is substantially reduced, it is an illusion to believe that infrastructure will ever catch up.

Amenity for people in our major cities is being eroded through increasing congestion and road tolls, declining housing affordability and loss of green space. The whole country is having to bear the growing infrastructure costs.

The report estimates that each additional person requires at least $100,000 worth of additional public infrastructure to maintain the current standard of living. Governments have been trying to catch up with a backlog of infrastructure that developed during the early part of this century. Some progress is being made but we will be forever trying to catch up to cater for the new residents.

The Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics estimated that congestion costed the Australian economy $16.5 billion in 2015. Moreover, without major policy changes, congestion costs are projected to reach $27 to $37 billion by 2030. Similarly, Infrastructure Australia, in its 2019 infrastructure audit, estimated that the annualised cost of traffic congestion and public transport crowding in Australia would rise from $19 billion in 2016 to $39.6 billion in 2031. These congestion pressures will be particularly acute in Sydney and Melbourne.

The cold hard truth is that the quantity of infrastructure investment required for a big Australia is mind-boggling.

The volume of population growth into Sydney and Melbourne needs to be put into perspective:

- It took Sydney roughly 210 years to reach a population of 3.9 million in 2001. Yet the official medium projection by the ABS has Sydney reaching roughly 2.5 times that number of people in only 65 years.

- It took Melbourne nearly 170 years to reach a population of 3.3 million in 2001. The official medium ABS projection, however, has Melbourne’s population tripling that number in only 65 years.

In the face of these unprecedented numbers, the key difference between then and now needs to be underlined: unlike the post-war period, it is no longer easy to further expand the capacities of our largest cities. What was an abundant supply of cheap frontier land in the 1950s and 1960s is now well and truly built-out. Both cities are now sprawling metropolises with greenfield land in short supply. Ever-longer commutes erode productivity, and ever-greater distances between rich and poor neighbourhoods entrench disadvantage. New infrastructure investment necessarily requires costly solutions like land acquisitions and tunnelling in order to retrofit projects into existing suburbs.

Some recent examples are stark. The WestConnex project in Sydney will reportedly cost $17 billion for 33 km ($515 million per kilometre) while Melbourne’s West Gate Tunnel is expected to cost $6.7 billion for five kilometres of highway ($1.34 billion per kilometre). In contrast, the 155 km Woolgoolga to Ballina highway upgrade, a surface road, costs $4.9 billion, or just $32 million per kilometre (approximately 16 times less than WestConnex, and 42 times less than the West Gate Tunnel, on a per kilometre basis). And yet, with all of this current and proposed investment, of increasing orders of magnitude, congestion is still expected to increase.

The Productivity Commission has reported several times on the costs and benefits of immigration and has found little if any net benefit for the existing population. It has also added an important caveat, namely that it has not taken the infrastructure or environmental costs into its analyses because of the complexity of doing so

There are two myths that the government keeps on spruiking as the solution. Again these were the findings of a COAG report.

Invest in Infrastructure and Plan Better

The SPA report demonstrates that this is impossible with the current growth rate.

Settle New Migrants in Regional Areas

There is no way of keeping migrants in regional areas when there is not enough employment. Cutting Sydney’s population by 40,000 would not be noticed but the addition of that many people to a centre like Orange would double its current numbers. Most regional centres do not have enough water supply to cater for a large increase in population. Much of regional Australia is located far away from the ocean, meaning that desalination of seawater is not an option, and large-scale desalination of groundwater for inland towns is unlikely to be feasible or ecologically sustainable.

They are all Fiddling while the World Burns

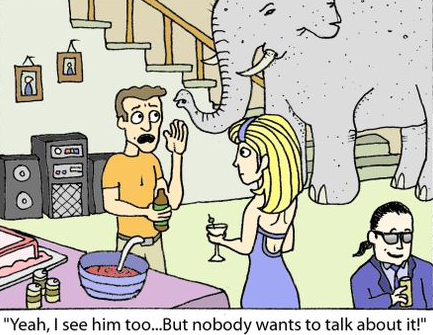

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

Part of that mobilisation will surely be the recognition that population growth is a major cause of ongoing warming. Halve the population and we roughly halve much of the pollution causing warming as well as other pollution such as plastics.

That brings us to what’s happening in Australia.

With an average of about 12.5 million people over the past 220 years we have degraded our major river systems, caused a terrible list of plant and animal extinctions, degraded our topsoils and more and are now busily overpopulating our major cities - with consequent physical and social consequences.

Our current annual rate of population growth of 1.7% will lead to doubling every 42.5 years. That means 50 million in 2061, 100 million in 2104 and 200 million in 2146 and so on.

You would think that those numbers would be enough to promote some discussion of where we are heading and where we want to head and how to go about it. But no, the Coalition, Labor and the Greens, along with our major environmental groups such as the ACF and NCC, all seem intent on ignoring the elephant and ensuring further degradation and destruction of the Australian natural world.

Why is this thus? We think there are a few reasons.

Firstly there is huge ignorance around the maths of exponential growth. It’s amazing to find so many educated, even scientifically educated, people who have not a clue about the consequences of 1.7% growth.

Secondly, the mainstream media and political world has insisted in conflating population growth with protecting the borders and racism. You talk about less population and so many assume that you are dog-whistling and really mean that we don’t want those refugees. The ABC has a terrible record in this regard.

Thirdly, the big end of town, those whose lobbyists haunt the corridors of our parliaments, cheque books in hand, has convinced many that without economic growth we shall all become destitute. That is simply self-serving rubbish that suits their economic interests. More people mean more housing, more furnishings, and more of most things. It’s not the environment they worry about – it’s their never-ending need for more economic activity and more profit.

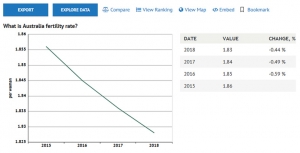

Australia’s fertility is now about 1.83 which will eventually produce a declining population because it is below the replacement level of 2.1. In addition, some 50,000 people leave Australia permanently every year. This means that we can accept 70,000 immigrants per year and eventually stabilise our population. We should do so. There is plenty of room there for refugees.

STEP has never dog-whistled!

It’s hard, however, to know how we shall ever start to manage the situation so long as none of the elites are prepared to discuss it and so long as the environmental organisations don’t have the guts to confront it.

We have been writing about population for over thirty years and much more detail can be gleaned from our Position Paper on Population.

By John Burke, former president of STEP and chief author of STEP’s Position Paper on Population, has written this update on the population issue.

City Populations

There has been much media interest in the report that Sydney's population has reached 5 million. What has also been reported is that Melbourne’s population is growing faster than Sydney’s and may soon exceed it.

Sydney

The problem I have with this is that Sydney includes the Central Coast and the Blue Mountains, but not Wollongong. I don't advocate including Wollongong but leaving out the other two plus the Wollondilly Shire (Picton) we have 5.25 – 0.33 – 0.08 – 0.05 = 4.79 million. We could go further and leave out the farther reaches of Hornsby, Baulkham Hills and other local government areas.

Melbourne

Melbourne includes the Mornington Peninsular (0.16 million) which is debatable. Other areas should also be removed (allow 0.05 million). So, 4.67 – 0.16 – 0.05 = 4.46 million which is 93% of Sydney’s population.

Distortions

Part of the problem for the Australian Bureau of Statistics is that the outer suburban local government areas cover large areas of peripheral rural land. The Sydney map at a guess is at least 75% rural and this leads to massive distortions when people try to compare densities.

This data below (from Population Australia) is rubbish. Population Australia is a website specialising in research for Australia population growth trends and estimation. It is not clear who is behind this group but the data seems to be coming from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

More on this some other time.

Position | City | Population density |

1 | Melbourne | 453/km2 |

2 | Adelaide | 404.205/km2 |

3 | Sydney | 400/km2 |

4 | Perth | 317.736/km2 |

5 | Canberra | 173.3/km² |

6 | Brisbane | 145/km2 |

7 | Hobart | 124.8/km2 |

8 | Darwin | 44.976/km2 |

Jim Wells has been delving into published statistics that are more than meets to eye.

The Decoupling Delusion: Rethinking Growth and Sustainability

Our economy and society ultimately depend on natural resources: land, water, material (such as metals) and energy. But some scientists have recognised that there are hard limits to the amount of these resources we can use. It is our consumption of these resources that is behind environmental problems such as extinction, pollution and climate change.

Even supposedly 'green' technologies such as renewable energy require materials, land and solar exposure, and cannot grow indefinitely on this (or any) planet.

Most economic policy around the world is driven by the goal of maximising economic growth (or increase in gross domestic product – GDP). Economic growth usually means using more resources. So if we can’t keep using more and more resources, what does this mean for growth?

Most conventional economists and policymakers now endorse the idea that growth can be 'decoupled' from environmental impacts – that the economy can grow, without using more resources and exacerbating environmental problems.

Even the then US president, Barack Obama, in a recent piece in Science argued that the US economy could continue growing without increasing carbon emissions thanks to the rollout of renewable energy.

But there are many problems with this idea. In a recent conference of the Australia-New Zealand Society for Ecological Economics (ANZSEE), we looked at why decoupling may be a delusion.

The Decoupling Delusion

Given that there are hard limits to the amount of resources we can use, genuine decoupling would be the only thing that could allow GDP to grow indefinitely.

Drawing on evidence from the 600-page Economic Report to the President, Obama referred to trends during the course of his presidency showing that the economy grew by more than 10% despite a 9.5% fall in carbon dioxide emissions from the energy sector. In his words:

…this 'decoupling' of energy sector emissions and economic growth should put to rest the argument that combating climate change requires accepting lower growth or a lower standard of living.

Others have pointed out similar trends, including the International Energy Agency which last year – albeit on the basis of just two years of data – argued that global carbon emissions have decoupled from economic growth.

But we would argue that what people are observing (and labelling) as decoupling is only partly due to genuine efficiency gains. The rest is a combination of three illusory effects: substitution, financialisation and cost-shifting.

Substituting the Problem

Here’s an example of substitution of energy resources. In the past, the world evidently decoupled GDP growth from buildup of horse manure in city streets, by substituting other forms of transport for horses. We’ve also decoupled our economy from whale oil, by substituting it with fossil fuels. And we can substitute fossil fuels with renewable energy.

These changes result in 'partial' decoupling – that is, decoupling from specific environmental impacts (manure, whales, carbon emissions). But substituting carbon-intensive energy with cleaner, or even carbon-neutral, energy does not free our economies of their dependence on finite resources.

Let’s get something straight: Obama’s efforts to support clean energy are commendable. We can – and must – envisage a future powered by 100% renewable energy, which may help break the link between economic activity and climate change. This is especially important now that President Donald Trump threatens to undo even some of these partial successes.

But if you think we have limitless solar energy to fuel limitless clean, green growth, think again. For GDP to keep growing we would need ever-increasing numbers of wind turbines, solar farms, geothermal wells, bioenergy plantations and so on – all requiring ever-increasing amounts of material and land.

Nor is efficiency (getting more economic activity out of each unit of energy and materials) the answer to endless growth. As some of us pointed out in a recent paper, efficiency gains could prolong economic growth and may even look like decoupling (for a while), but we will inevitably reach limits.

Moving Money

The economy can also appear to grow without using more resources, through growth in financial activities such as currency trading, credit default swaps and mortgage-backed securities. Such activities don’t consume much in the way of resources, but make up an increasing fraction of GDP.

So if GDP is growing, but this growth is increasingly driven by a ballooning finance sector, that would give the appearance of decoupling.

Meanwhile most people aren’t actually getting any more bang for their buck, as most of the wealth remains in the hands of the few. It’s ephemeral growth at best: ready to burst at the next crisis.

Shifting the Cost onto Poorer Nations

The third way to create the illusion of decoupling is to move resource-intensive modes of production away from the point of consumption. For instance, many goods consumed in Western nations are made in developing nations.

Consuming those goods boosts GDP in the consuming country, but the environmental impact takes place elsewhere (often in a developing economy where it may not even be measured).

In their 2012 paper, Thomas Wiedmann and co-authors comprehensively analysed domestic and imported materials for 186 countries. They showed that rich nations have appeared to decouple their GDP from domestic raw material consumption, but as soon as imported materials are included they observe 'no improvements in resource productivity at all'. None at all.

From Treating Symptoms to Finding a Cure

One reason why decoupling GDP and its growth from environmental degradation may be harder than conventionally thought is that this development model (growth of GDP) associates value with systematic exploitation of natural systems and also society. As an example, felling and selling old-growth forests increases GDP far more than protecting or replanting them.

Defensive consumption – that is, buying goods and services (such as bottled water, security fences, or private insurance) to protect oneself against environmental degradation and social conflict – is also a crucial contributor to GDP.

Rather than fighting and exploiting the environment, we need to recognise alternative measures of progress. In reality, there is no conflict between human progress and environmental sustainability; well-being is directly and positively connected with a healthy environment.

Many other factors that are not captured by GDP affect well-being. These include the distribution of wealth and income, the health of the global and regional ecosystems (including the climate), the quality of trust and social interactions at multiple scales, the value of parenting, household work and volunteer work. We therefore need to measure human progress by indicators other than just GDP and its growth rate.

![]() The decoupling delusion simply props up GDP growth as an outdated measure of well-being. Instead, we need to recouple the goals of human progress and a healthy environment for a sustainable future.

The decoupling delusion simply props up GDP growth as an outdated measure of well-being. Instead, we need to recouple the goals of human progress and a healthy environment for a sustainable future.

James Ward, Lecturer in Water & Environmental Engineering, University of South Australia; Keri Chiveralls, Discipine Leader Permaculture Design and Sustainability, CQUniversity Australia; Lorenzo Fioramonti, Full Professor of Political Economy, University of Pretoria; Paul Sutton, Professor Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Denver, and Robert Costanza, Professor and Chair in Public Policy at Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Greater Sydney Strategy

It's important that as many people as possible comment on the Greater Sydney Strategy and the North District Plan by 31 March 2017.

Towards Our Greater Sydney 2056 is a 40 year vision that spells out the anticipated rate of growth and framework for employment and population distribution. How this is done will ultimately determine the long-term impacts on our natural areas, STEP’s chief focus.

For a city the size of Sydney, strategic planning over a 40 year period is important. However as outlined below there are matters of serious concern.

High Rate of Growth

On p8 there is this statement:

Greater Sydney is experiencing a step change in its growth with natural increases (that is an increase in the number of births) a major contributor. We need to recognise that the current and significant levels of growth, and the forecast higher rates of growth are the new norm rather than a one-off peak or boom.

Given the clear impacts of high growth rates on our urban amenity this statement needs closer scrutiny.

Refer to the table below for the projected growth rates and the figure below for the net overseas migration component.

| Region | Population 2011 | Projected population | ||

| 2036 | Change 2011–36 | % change 2011–36 | ||

| Greater Sydney | 4,286,350 | 6,421,950 | 2,135,650 | 49.8% |

| Rest of NSW | 2,932,200 | 3,503,600 | 571,400 | 19.5% |

From the figures the total projected increase in population in NSW from 2011–36 is around 2.7 million. Of this, for the same period, the total from net overseas migration is around 1.7 million, leaving the natural growth at around 1 million.

A recent report by the Planning Institute of Australia on population trends, Through the Lens: Megatrends Shaping our Future (p12) concluded:

Overseas migration continues to be the biggest contributor to population growth.

Net overseas migration for Australia since 1976 is shown in the lower figure. On p12 it says that:

Of the three basic factors determining population growth (fertility/births, mortality/deaths and migration) the net migration rate is most subject to policy intervention, and thus the most uncertain in future projections.

Since the net migration rate is the primary determinant of Australia’s population growth and is controlled by government policy, it is clearly possible to regulate the overall population growth rates of Australia to ensure they are at acceptable levels and anticipated benefits are broadly realised.

Since the net migration rate is the primary determinant of Australia’s population growth and is controlled by government policy, it is clearly possible to regulate the overall population growth rates of Australia to ensure they are at acceptable levels and anticipated benefits are broadly realised.

The regulation of inflation by the Reserve Bank has proved beneficial relative to an unregulated economy. Regulation of Australia’s overall population level and age structure through adjustment of net migration targets by a Federal government agency could prove beneficial to planning within Australia. This agency has to work in concert with state governments that bear the brunt of the implementation consequences.

High growth rates are resource intensive, difficult to manage and can lead to significant long-term environmental impacts. In the past these have included a higher proportion of defective buildings, lags in required new infrastructure with traffic congestion increasing and damage to bushland and watercourses from greater urban stormwater run-off.

The current proposed annual growth rates of around 1.6% are too high and need to be reduced to the more manageable levels in the previous three decades of around 1%. The Mercer World’s Most Liveable Cities ranking indicates that beyond a population of around 6 million liveability declines. Sydney has to recognise that growth cannot be infinite and ultimately must plan for a zero net growth future.

The Greater Sydney Commission may not have a say in the growth projections but we think people should be able to express their views through the current consultations process and local federal and state MPs.

Urban Renewal

On p8 it states that the shorter term need for additional new housing capacity is greatest in the North and Central Districts. While this will lead to more high-rise development along the railway line it is important that urban conservation corridors are retained.

For example it is possible to walk from Gordon, Killara and Roseville Stations through high quality urban conservation areas to the bushland that leads to Garigal National Park. The value of these conservation corridor links from railway stations to our national parks can only increase with time.

Medium Density Infill Development

On p9 it states:

Many parts of suburban Greater Sydney that are not within walking distance of regional transport (rail, light rail and regional bus routes) contain older housing stock. These areas present local opportunities to renew older housing with medium density housing. Medium density housing is ideally located in transition areas between urban renewal precincts and existing suburbs, particularly around local centres and within the 1 to 5 km catchment of regional transport.

A 1 to 5 km catchment from the railway stations and regional bus routes would include virtually all of the North Shore. Future medium density in these areas is likely to be fast-tracked by developers using the NSW government’s proposed Complying Medium Density Housing Code (CMDHC).

Provided prescribed standards are met this could allow building density increases by as much as a factor of two without the need for consent. Because of its indiscriminate nature, for those areas impacted by the code, it could lead to increases in dwelling numbers significantly in excess of those planned for.

The CMDHC is proposed in extensive single dwelling R2 zones for those councils where multi-dwelling housing or dual occupancy is permissible in this zone. If one council allows multiple dwellings it will flow through to all the original member councils when they amalgamate.

Examination of the relevant LEPs indicates all the amalgamated councils in the North District will be impacted with the exception of Hornsby–Ku-ring-gai. STEP strongly opposes application of CDMH in any residential zone other than the medium density R3 zone.

Economic Priorities

On p7 there is a focus on the economic growth from inbound tourism. This would be a serious concern if our bushland and national parks are treated as assets for commercialisation. Sensitive natural bushland areas can easily be damaged from overuse and need protection. Private leasehold of areas with existing bushland and clearance for accommodation should not be supported.

We can Achieve Sustainability – but not without Limiting Growth

Mark Diesendorf, UNSW Australia

Can Australians be sustainable and enjoy endless economic growth? It’s not likely.

Issues of Major Concern for NSW

The population of the Sydney metropolitan area is estimated to grow by 1.6 million people by 2031. According to the NSW Government, Sydney will need 664,000 additional dwellings by 2031. This dramatic expansion is being driven by the Australian Government’s insane promotion of high immigration in pursuit of its unsustainable growth agenda. The NSW Government’s response is A Plan for Growing Sydney.

Rapid Population Growth – Witches Hats Claim another Casualty

Media Release 17 September 2015, The Hon Kelvin Thomson, Federal Member for Wills.