Newsletter blog

Children categories

2040 – Join the Regeneration

STEP is supporting the screening of the film 2040 at Roseville Cinema. Booking is essential. We need a minimum of 68 bookings before the screening can go ahead. Your payment will be refunded if this number is not reached.

The previous screening organised by Ku-ring-gai Council in July was booked out.

2040 is a hybrid feature documentary that looks to the future, but is vitally important NOW! Award-winning director Damon Gameau (That Sugar Film) embarks on journey to explore what the future could look like by the year 2040 if we simply embraced the best solutions already available to us to improve our planet and shifted them rapidly into the mainstream.

Structured as a visual letter to his 4-year-old daughter, Damon blends traditional documentary with dramatised sequences and high-end visual effects to create a vision board of how these solutions could regenerate the world for future generations.

Citizen Science Project - Dead Tree Detective

Western Sydney University and the University of New England have set up a Citizen Science Project called the Dead Tree Detective.

The aim of the project is to collect observations of dead or dying trees around Australia. It sounds a bit grim, but knowing where and when trees have died will help us to work out what the cause is, identify trees that are vulnerable, and take steps to protect them.

This project will allow people Australia-wide to report observations of tree death. In the past, there have been many occurrences of large-scale tree death that were initially identified by concerned members of the public such as farmers, bushwalkers, bird watchers and landholders. Collecting these observations is an important way to monitor the health of trees and ecosystems.

All you need is a smart phone with a camera and GPS. It is also possible to report on paper by asking for a survey form by emailing This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

The leader of the project, Prof Belinda Medlyn wants to get better data about how trees respond to drought.

How our native plants cope with these changes will affect (among other things) biodiversity, water supplies, fire risk and carbon storage. Unfortunately, how climate change is likely to affect Australian vegetation is a complex problem, and one we don’t yet have a good handle on.

Threatened Species Children’s Art Competition

STEP has supported the Threatened Species Children’s Art Competition since 2017. The competition has been a great success and has now expanded to Victoria, and other states are expressing interest.

Administration has now been taken over by the Humane Society International – the largest worldwide charity caring for animals.

Children choose a threatened native species, then create a drawing or painting of it with an accompanying short explanation of their work. Entries close on 2 August 2019.

Seventy NSW finalists will be chosen for a two-week exhibition in Sydney, with winners announced at Parliament House Sydney on 6 September 2019.

Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest Declared Critically Endangered

The NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee, established under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, has made a Final Determination to list Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (STIF) in the Sydney Basin Bioregion as a critically endangered ecological community. This classification already applies under the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act.

The highest threat category is now applied because STIF has experienced large:

- reductions in geographic distribution

- degrees of environmental degradation

- disruptions of biotic processes and interactions

There is an estimated 2,940 ha of STIF remaining, or less than 10% of the estimated original distribution.

Remnants of STIF are poorly represented in the formal reserve network, and unreserved areas are subject to the threat of vegetation clearing. The total area under reservation is estimated to be 570 ha, equivalent to less than 2% of the estimated pre-1750 distribution or 20% of the remaining extent.

Remnants of STIF have historically been subjected to a range of anthropogenic disturbances including logging, grazing by domesticated livestock and burning at varying intensities.

Remnants are typically small and fragmented and are susceptible to continuing attrition through clearing for routine land management practices due to the majority of remnants being located in close proximity to rural land or urban interfaces.

Applications to the NSW Land and Environment Court demonstrate that there is ongoing pressure to clear STIF in the course of developing private properties or for the establishment of asset protection zones.

STIF is subject to ongoing invasion by an extensive range of naturalised plant species. Weed invasion is exacerbated by the proximity of remnants to areas of rural and urban development and the associated influx of both weed propagules from gardens and nutrients contained in stormwater runoff, dumped garden waste and animal droppings.

John Martyn Research Grant Award for 2019

We are very pleased to announce that the John Martyn Research Grant for 2019 has been awarded to Gabriella Hoban. Gabriella’s research project is entitled Soil Characteristics as Indicators of Restoration Trajectories in Urban Woodlands. This subject is highly relevant to STEPs aims to restore degraded ecological communities.

She has provided us with this description of her project.

Hi! I’m Gabby. I am an honours student at the University of New South Wales. I love ecology, ecological restoration and conservation and have a slight obsession with plants.

For my honours project I will be studying the effect of soil characteristics on restoration trajectories in urban woodlands. My research will be based in western Sydney within the Cumberland Plain Woodland, a critically endangered vegetation community. In this region, a concentration of threatened species and ecological communities overlap with intense development pressure.

Through my project I aim to quantify the relationship between the abundance of exotic and native plant species in relation to soil constituents in bushland reserves with agricultural land use legacies. Soil samples will be collected and the effect of soil properties on restoration trajectories will be determined.

My research will build on existing data from long-term study sites established in 1989. This research provides an exciting opportunity to examine long term trends in regenerating bushland.

I hope this research can inform conservation efforts not only at this site, but also similar grassy reserves recovering from legacies of former agricultural land use that span a large area across south-eastern Australia.

Thank you to STEP and its members for the opportunity.

Last Attempt to Stop the Mirvac Development Plans for the IBM Site

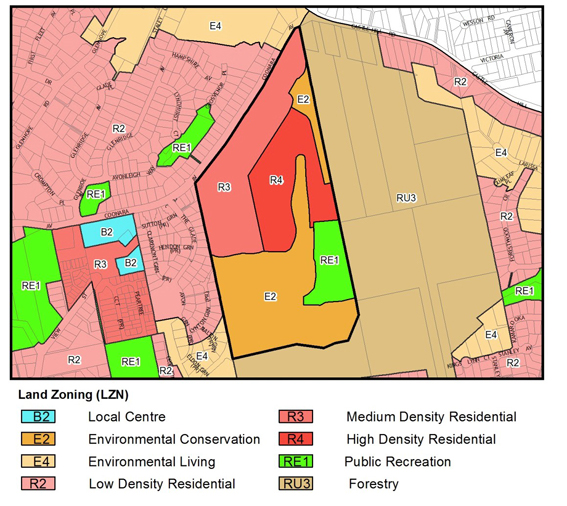

The final deadline was set at 31 May for submissions on the Hills Council’s applications to the NSW government to change the zonings in their local environment plan and insert some special provisions in the development control plan. These changes will facilitate development on the land owned by Mirvac that currently contains the old IBM corporate headquarters on the corner of Coonara Road and Castle Hill Road in West Pennant Hills next to the Cumberland State Forest.

The basic framework of the proposals is unchanged from earlier plans described in STEP Matters (Issue 198). The main purpose of the council application at this stage is to facilitate the development of 600 dwellings. Ancillary aspects are that, if the housing development proceeds, Mirvac will sign a voluntary agreement to allow the existing playing field on the land to become public open space and pay for the development of a soccer field with synthetic turf and the necessary public access road.

The design of the housing development will be subject to further scrutiny at the development application stage but if these current plans are approved, the basic framework will be set in concrete (lots of it!).

Even though part of the site is currently developed as a corporate park, these buildings are surrounded by mature tree plantings. The majority of the site is classified as Blue Gum High Forest or Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest, both critically endangered. This is a unique opportunity to preserve one of the few remaining areas of high quality vegetation and its associated fauna habitat in north-western Sydney. Its proximity to Cumberland State Forest adds to the value of this preservation through its connectivity and boosting of resilience of the vegetation.

Hence STEP is opposed to the whole development proposal.

Future of the forested area

The future management of the large forested area that is to be zoned E2 (environmental conservation) which contains critically endangered ecological communities and fauna, is completely unknown. The development control plan amendment relating to the site refers to the residents as being responsible for the cost of maintenance of the 'significant vegetation'. This is totally unrealistic.

It is essential that a stewardship or conservation agreement be established defining responsibilities and funding of management together with a vegetation management plan. This should be in place before any dwellings are occupied.

As the E2 land will be for the benefit of the whole local community, not just the residents of the Mirvac developments, it is appropriate that the Hills Council be responsible for its management.

Synthetic playing field

The proposal for the synthetic playing field should not go ahead until the environmental impact of the use of this surface is thoroughly assessed. A detailed analysis is required of the impact on the bushland below the field of:

- stormwater runoff from the hard surface

- runoff of degraded synthetic grass and substrate pieces

- the loss of soil biota under the artificial surface

- the risk from a fire in the surrounding bushland spreading to the field

- conversely, the surface itself is mostly made of rubber and will be much hotter than in the surrounding vegetated areas, so what impact will this have on the bushland and wildlife?

Of course no floodlighting should be allowed so close to bushland that is home to several nocturnal species such as the Powerful Owl and several species of bats.

Development plans

The image at the top of the page shows the proposed layout of the development. The medium density housing area (200 dwellings) is along the edges of the site while the high density zone (flats up to six stories) is lower down next to the forested areas.

The main argument from Mirvac in favour of the development is its proximity to the new Cherrybrook Metro Station. Residents will however have to walk up a steep hill and cross Castle Hill Road to get to the station. The shortest possible walk is 800 m. The other side of Castle Hill Road which is in the Hornsby Council area is currently zoned low-density residential that will no doubt be planned for higher density development in the future as the station is now operating.

Overdevelopment

The major reason for objections to the proposals is the level of development. The residents of West Pennant Hills have rallied strongly against the proposals. Over 4,000 objections have been received by the Hills Council. They are concerned about the increase in traffic on already congested roads as well as the environmental impact of the development.

The main point is that the existing IBM corporate park is a valuable asset. The buildings should not be knocked down. With a bit of imagination alternative uses could be found that will not lead to destruction of the mature native vegetation that surrounds the buildings and the car park.

In any case the council and Mirvac have not demonstrated that there is a need for this huge housing area. We note that the Department of Planning document Cherrybrook Structure Plan: Vision for Cherrybrook Station Surrounds (September 2013) does not envisage any residential development on the site. Increases in housing are planned for neighbouring areas north and further west of Castle Hill Road with a total number of new dwellings planned of 3,200 by 2036.

The plan is an example of the notorious spot re-zonings that have plagued development in Sydney. A developer comes up with a plan that is outside the planning guidelines. The local council knocks it back so the developer is able to go directly to the Department of Planning to gain approval via the Gateway Process. The new planning minister, Rob Stokes, has stated that this system will not continue but we will have to see how that can come about.

As Hornsby Council says in their submission:

Any decision for this site should be deferred until a precinct-wide structure plan or strategy is adopted for all the land parcels surrounding the Cherrybrook Metro Station.

...

The proposal by Mirvac to redevelop the subject property for residential purposes is likely to trigger further owner/developer-led spot rezoning applications in the area. This would lead to an ad hoc approach to land use planning for the Metro Station precinct. The process would undermine the planning framework for both councils and lead to poor outcomes for the Cherrybrook community.

Housing plan is overdeveloped

The documents indicating the layout of the medium-density housing precinct show houses that are crammed together, some on blocks as small as 86 m2 that are only 4 m wide. Even with some of the wider lots most of the street will be taken up by driveway access.

There will be little space for street trees. The front and back yards will also be too small for trees to grow with a beneficial canopy.

The design of the subdivision needs to take account of the need for liveability of streets in the face of current heat in summer and expected increases with climate change.

There are also several other concerns about the details of the development and how it will impact on the surrounding forest. These relate to clearing of riparian zones and impingement of asset protection zones into the E2 area and Cumberland State Forest.

We have covered several of these concerns in previous comments on this proposal. They are very concerning but basically STEP is opposed to the development in its entirety.

Conclusion

Mirvac’s website reveals the company’s Biodiversity Policy. The policy states:

At Mirvac, we aim to be an overall positive contributor to environmental sustainability. We firmly believe that responsibly managing our biodiversity impacts will enable us to strategically assess biodiversity-related risks and opportunities and anticipate and respond proactively to emerging regulations and societal expectations.

Mirvac’s plans for the IBM site are clearly not compatible with their Biodiversity Policy.

Let’s Introduce Vehicle Fuel Efficiency Standards and Save Money Too

The transport sector is Australia’s second fastest growing source of carbon dioxide emissions and yet we still don’t have any standards which apply to new vehicle fuel efficiency.

Road transport contributed 16% to total CO2 emissions in 2000 and this grew to 18% in 2010 and 21% in 2016.

We are the only OECD country with no minimum fuel standard while more than 80% of the global vehicle market has adopted fuel standards. We have had standards for many years relating to other vehicle emissions such as nitrous oxides, carbon monoxide and particulates.

Standards in other countries

The EU applied mandatory standards from 2009 requiring a light vehicle fleet average of 130 g CO2/km by 2015 and 95 g/km by 2020–21.

These standards have been further developed requiring a reduction by 15% by 2025 and 37.5% by 2030 relative to 2020–21. Standards will also be applied to heavy vehicles.

The USA has had voluntary standards since 1975 that have not been effective. In 2012 standards were introduced including a reduction by 3% each year after 2012 applied to each manufacturer. They are enforced with the potential of the loss of licence to sell vehicles. The effective standard is slightly higher than applies to the EU. However President Trump is now threatening to loosen the standards.

Testing methods are problematic

The sources used for this article comment on ongoing issues with the testing methods being used to monitor vehicle fuel use.

The standard methods used in Europe were developed in the 1970s. They are called the New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) and they have been found to be unrealistic because they assume that the car is being driven at a constant speed with mild acceleration. Actual consumption that has been tested in real conditions show the gap is getting worse and is now believed to be about 40%.

The sources don’t explain why the gap is getting worse apart from the legal methods of manipulating the tests, e.g. by using low-resistance tyres. The latest EU standards will require cars to have on-board monitoring systems in future.

Clearly there is a need for proper testing of on-road vehicle emissions. One wonders about the accuracy of the greenhouse gas reporting for Australia’s transport emissions. The same applies to reporting by other countries.

The standards are applied on a fleet wide basis but then manufacturers have to apply the standard to their individual range of vehicles. The projection of future emission levels requires an estimate of the nature of the vehicle fleet that is a combination of several cohorts of ages of vehicles plus the average distances travelled by each type of vehicle.

Australia’s experience

The current situation is that in 2017 Australia’s light passenger average CO2 emissions were 172 g/km compared with 118.5 g/km in the EU. In the case of light commercial vehicles Australia’s average was 222 g/km compared with 164 g/km in the EU.

In addition to the lack of efficiency standards, according to a report from Transport Energy/ Emissions Research [1] several other factors contribute to Australia’s higher vehicle emissions:

- Use of heavier and greater engine capacity cars such as SUVs (even in comparison with the USA). It is reported that in 2017 the average fuel use in Australia was 20% higher than in the USA. This trend is getting worse.

- Use of automatic transmissions that are reported to be less fuel efficient.

- Greater distances travelled. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that total travel by passenger vehicles in Australia was 142 billion kilometres in 2000. This has been growing to 176 billion kilometres in 2016, an increase of 24%.

- The most fuel efficient model choices in Australia are not as efficient as in Europe leading to the suggestion that manufacturers are taking advantage of our lack of mandatory standards.

- Our vehicle fleet is older than in other countries and turnover is slower so it takes longer for the benefit of newer, more fuel-efficient vehicles to flow through to the fleet as a whole. Conversely driving a vehicle for a longer period could produce lower emissions when allowance is also made for the emissions during manufacture.

It is also suggested that Australians are paying paying about 30% more for fuel than they should (provided better fuel efficiency doesn’t encourage more driving).

Australia’s attempts to introduce standards

Australia has had voluntary efficiency standards since 1978 that were equivalent to 195 g CO2/km (2000) and 161 g CO2/km (2010) but these have not been achieved.

In 2010, the ALP government decided that mandatory CO2 emissions standards would apply to new light vehicles from 2015, i.e. a national fleet wide average of 190 g/km in 2015 and 155 g/km in 2024. However, the change in government in 2013 meant the standards would not see the light of day.

Several reports have been written analysing the options for introducing standards.

The Climate Change Authority produced a report in December 2016 that proposed that the first phase of mandatory standards be introduced with effect from 2018, by which time local manufacture of automobiles was expected to have ceased.

The standards would progressively reduce CO2 emissions from new light vehicles to 105 g/km in 2025, almost half the then current level of 192 g/km. This 2025 standard would broadly bring Australia into line with the USA and still trail the tighter EU targets by several years.

A Ministerial Regulation Impact Statement found that the introduction of a standard of 105 g/km phased in over 2020–25 would cost $16.2 billion compared with no standards but would lead to:

- national fuel savings of $27.5 billion

- reduce greenhouse gas emission by 65 Mt by 2030

- create an overall net benefit to the economy of $13.9 billion

This calculation allowed for a cost of carbon emissions of about $50/tonne.

The Automotive Association has lobbied against the proposal on the grounds that cars will be more expensive. Implementation of a standard to reduce CO2 emissions to 105 g/km is estimated to increase the average cost of a new car in 2025 by about $1500. This, however, would be offset several times by fuel savings of about $8500 over the life of the vehicle, leaving motorists better off.

How about electric vehicles?

The rollout of electric vehicles in Australia is being held back by their cost and lack of recharging stations. Labor’s election proposal to require that 50% of new passenger vehicles sold be electric vehicles by 2030 was hysterically dismissed by Scott Morrison. He claimed the policy would make life impossible for tradies as the ute would be uneconomic and it would spell the end of the weekend trip away in the SUV.

Of course this was all nonsense as the cost of electric vehicles is coming down rapidly and is expected to be similar to internal combustion engines by 2025. We might even revive the local manufacturing industry? In any case perhaps it would be a good idea to hire a large SUV for a weekend trip rather than driving these large vehicles around to drop the kids off at school or commute to work.

One question about the use of electric vehicles is the carbon emissions if they are being recharged using electricity from the current high use of coal-fired generation. The data I have found indicates that electricity consumption to run an electric vehicle could be 6–10 Kw h per 100 km. Currently Australia’s emissions from electricity generation is 800 g/Kw h. So that equates to carbon emissions from electric vehicles of 48–80 g/km.

Conclusion

The available evidence suggests that legislative action regarding vehicle CO2 emissions is long overdue. The federal government must take action to ensure total CO2 emissions from road transport are reduced by introducing emission standards and by taking several additional measures such as increasing public transport and reducing distances driven.

Introducing these new regulations quickly is a priority because it takes years for them to actually work their way through the market to the new vehicle fleet.

References

[1] Transport Energy/Emission Research Pty Ltd Vehicle CO2 Emissions Legislation in Australia – A Brief History in an International Context

Threat to a Common European Tree

The costly problem of ash dieback has been highlighted in New Scientist.

This fungal disease caused by Hymenoscyphus fraxineus was first detected in Britain in 2012 having crept across Europe from the east. Its origin is Asia and it affects the common ash Fraxinus excelsior. It's predicted to destroy more than 90% of the many million ash trees, killing saplings within a year of infection. Coming on top of Dutch elm disease and various infections of both English oak species, it's a concern in a country that has, through millennia, lost most of its native forests.

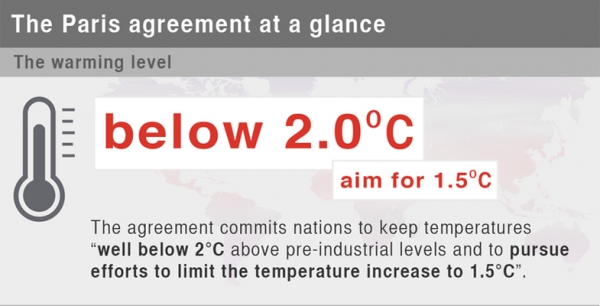

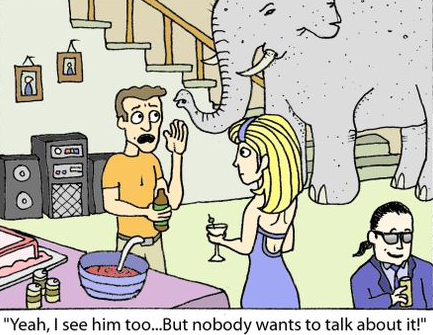

They are all Fiddling while the World Burns

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

When the USA became serious about WWII they brought about an amazing mobilisation of their entrepreneurial industrial potential. That is surely the way in which the fight against global warming will be conducted when we eventually wake up to the urgency. In the meantime most of the world’s leaders and most of the populace seems content enough to drift along ignoring that elephant in the room.

Part of that mobilisation will surely be the recognition that population growth is a major cause of ongoing warming. Halve the population and we roughly halve much of the pollution causing warming as well as other pollution such as plastics.

That brings us to what’s happening in Australia.

With an average of about 12.5 million people over the past 220 years we have degraded our major river systems, caused a terrible list of plant and animal extinctions, degraded our topsoils and more and are now busily overpopulating our major cities - with consequent physical and social consequences.

Our current annual rate of population growth of 1.7% will lead to doubling every 42.5 years. That means 50 million in 2061, 100 million in 2104 and 200 million in 2146 and so on.

You would think that those numbers would be enough to promote some discussion of where we are heading and where we want to head and how to go about it. But no, the Coalition, Labor and the Greens, along with our major environmental groups such as the ACF and NCC, all seem intent on ignoring the elephant and ensuring further degradation and destruction of the Australian natural world.

Why is this thus? We think there are a few reasons.

Firstly there is huge ignorance around the maths of exponential growth. It’s amazing to find so many educated, even scientifically educated, people who have not a clue about the consequences of 1.7% growth.

Secondly, the mainstream media and political world has insisted in conflating population growth with protecting the borders and racism. You talk about less population and so many assume that you are dog-whistling and really mean that we don’t want those refugees. The ABC has a terrible record in this regard.

Thirdly, the big end of town, those whose lobbyists haunt the corridors of our parliaments, cheque books in hand, has convinced many that without economic growth we shall all become destitute. That is simply self-serving rubbish that suits their economic interests. More people mean more housing, more furnishings, and more of most things. It’s not the environment they worry about – it’s their never-ending need for more economic activity and more profit.

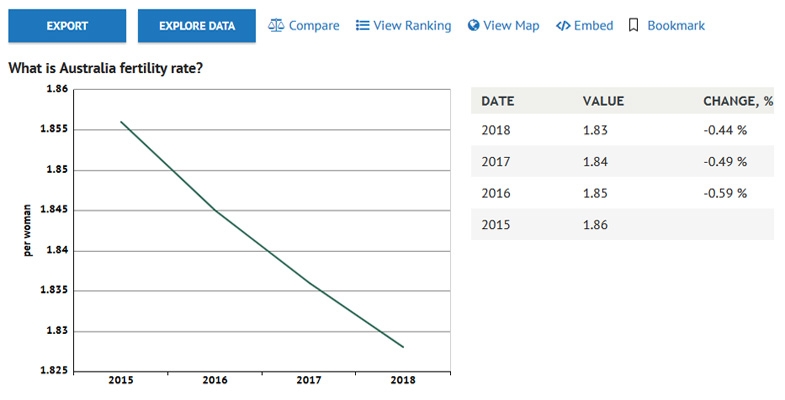

Australia’s fertility is now about 1.83 which will eventually produce a declining population because it is below the replacement level of 2.1. In addition, some 50,000 people leave Australia permanently every year. This means that we can accept 70,000 immigrants per year and eventually stabilise our population. We should do so. There is plenty of room there for refugees.

STEP has never dog-whistled!

It’s hard, however, to know how we shall ever start to manage the situation so long as none of the elites are prepared to discuss it and so long as the environmental organisations don’t have the guts to confront it.

We have been writing about population for over thirty years and much more detail can be gleaned from our Position Paper on Population.

By John Burke, former president of STEP and chief author of STEP’s Position Paper on Population, has written this update on the population issue.

The Future of Tasmanian Leatherwood

Visiting Tasmania at leatherwood flowering time in February was a nice experience apart from the weather. It has a perfumed flower likened to a four-petalled version of the five-petalled English wild dogrose. Tasmanian Leatherwood Eucryphia lucida, of honey fame, is a high rainfall, temperate rainforest species often found close to rivers (see the two pictures below taken at Pencil Pine Creek, Cradle Mountain). Driving along the Lyell Highway from Queenstown to Derwent Bridge we saw several beehive ‘mini cities’ in valleys, clearly exploiting the setting of the plant.

Australia has five species of Eucryphia, one of the commoner ones, E. moorei (see the picture at the top of the page and below) liking wet highland environments from the Illawarra to north-east Victoria.

The easiest place to see it locally in late summer is across the road from the Robertson Pie Shop where a windbreak hedge of small trees to 5 metres follows a fence line. We also saw it in flower at Fitzroy Falls, several specimens being scattered through the rainforest apron of the valley, though you wouldn't spot them without their flowers.

The latter setting is more typical for the tree and it seems to also like rocky sites – we located another tiny colony in Hawkesbury Sandstone on rocky Bundanoon Creek in Meryla State Forest south of Moss Vale.

The latter setting is more typical for the tree and it seems to also like rocky sites – we located another tiny colony in Hawkesbury Sandstone on rocky Bundanoon Creek in Meryla State Forest south of Moss Vale.

All Australian species grow in high rainfall, cool to warm temperate settings ranging from E. moorei of the Illawarra to E. wilkiei of the mountain cloud forests of North Queensland. But globally the picture of Eucryphia is bigger.

There are a further two species, E. cordifolia and E. glutinosa, from cool temperate rainforests of South America. And it turns out that there are striking similarities in the flavour of honeys from the Chilean E. glutinosa, known there as Ulmo, and that of Tasmanian Leatherwood. This is particularly extraordinary since the two continents severed their link via Antarctica more than 60 million years ago.

Eucryphia species have been cultivated in Australia, Europe and elsewhere, and include pink-flowered forms and hybrids. While the variety of rugged and inaccessible settings of common species like E. moorei may mean they are fairly safe, the northern species, E. jinksii and E. wilkiei are both local and endemic to their settings and are listed as threatened. E. wilkiei of Mt Bartle Frere cloud forests is especially vulnerable to climate change – horrendous heat records were set there this summer.

Of further concern, Tasmania was beset by wildfires this summer, particularly in the Huon Valley region south-west of Hobart. This, and the drought that amplified it, had a variety of negative effects on Leatherwood. There were multiple tree losses and flowering was weak: trees that did flower produced very little nectar. The suspected link to climate change is a cause for concern and Leatherwood may yet be another canary in the coal mine. Anyway, if you're looking to buy Leatherwood honey this year it won't easy or cheap.

References

Wikipedia

Blog: The Nature of Robertson

By John Martyn

How did the IPBES Assessment come up with the Figure of a Million Species at Risk of Extinction?

In May 2019 the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) published its global assessment of the state of the earth’s biodiversity and its prospects for change up to 2050. This is the first such report since the landmark Millennium Ecosystem Assessment published in 2005. The IPBES Assessment is the outcome of negotiations by 134 governments using data provided by 500 biodiversity experts from over 50 countries.

The aim of the IPBES Assessment is explained by its chair, Sir Robert Watson:

The loss of species, ecosystems and genetic diversity is already a global and generational threat to human well-being. Protecting the invaluable contributions of nature to people will be the defining challenge of decades to come. Policies, efforts and actions – at every level – will only succeed, however, when based on the best knowledge and evidence. This is what the IPBES Global Assessment provides.

It examines causes of biodiversity and ecosystem change, the implications for people, policy options and likely future pathways over the next three decades if current trends continue, and other scenarios.

My question is how did IPBES work out the number of species existing and at risk of extinction?

How many species are there?

Several different approaches have been used to estimate the actual total number of species on earth. Frankly it is impossible to know the number with any reasonable level of precision. The various methods give a very wide range of answers – from 3 million to over 100 million. Most of the more recent estimates based on thoughtful approaches are in range of 5 to 20 million.

The main point is to understand the relative level of extinction that could take place. We are finding new species all the time. There are frequent reports of excursions into rainforest finding lots of new beetles or other insect species. New species are even being found in our local area, viz Julian’s Hibbertia.

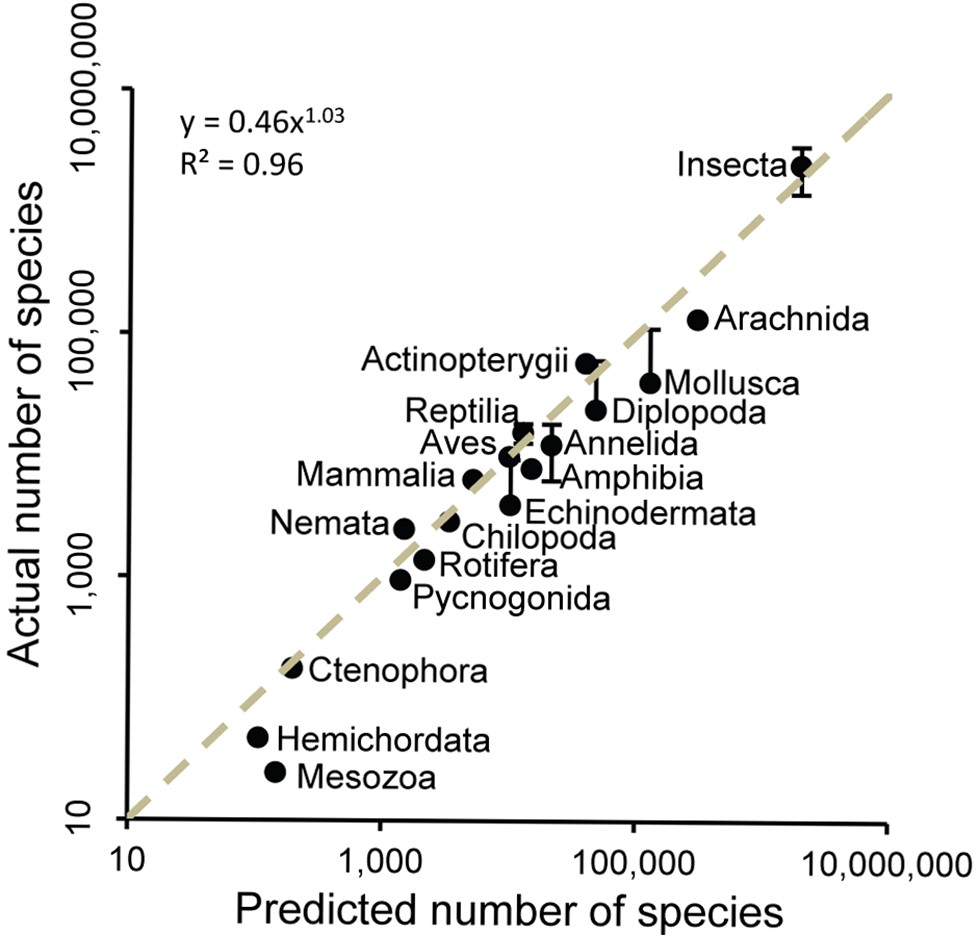

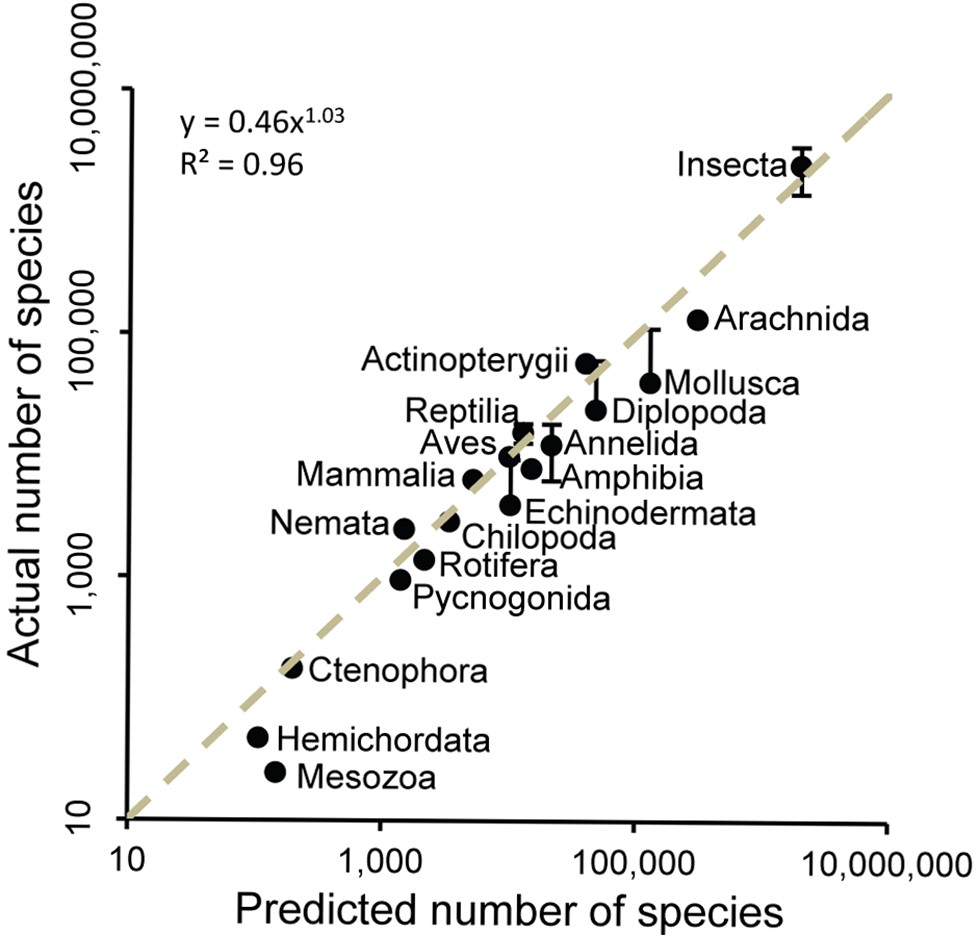

The report uses the results of a study published in 2011 [1]. The study uses data of past records showing how the knowledge of the number of phyla, classes, families, genii and species for each taxa have increased over time. For each level of the description hierarchy (phyla, class, etc) if fewer and fewer new types are being found then it is assumed that we are getting close to finding the final actual number. The method fits a regression line to the asymptotic graph of the known number over time to estimate the point where the line would reach the limit of increases. Then the phyla build into the number of classes and so on.

One argument in favour of this method is that species that are yet to be identified are living in small numbers or in niche areas so they are of less significance in terms of total life on the planet.

One argument in favour of this method is that species that are yet to be identified are living in small numbers or in niche areas so they are of less significance in terms of total life on the planet.

This approach was validated against well-known taxa such as mammals. When applied to all eukaryote kingdoms the approach predicted:

- ∼7.77 million species of animals

- ∼298,000 species of plants

- ∼611,000 species of fungi

- ∼36,400 species of protozoa

- ∼27,500 species of chromists

In total the approach predicted that ∼8.74 million species of eukaryotes exist on earth. Restricting this approach to marine taxa resulted in a prediction of 2.21 million eukaryote species in the world's oceans.

In spite of 250 years of taxonomic classification and over 1.2 million species already catalogued in a central database, the study’s results suggest that some 86% of existing species on earth and 91% of species in the ocean still await description.

How did IPBES derive the million at risk figure?

Species are defined as being at risk of extinction if their numbers are declining to the extent that the population may no longer be viable. They may not become totally extinct for a long time. For example, plants may live for many years but may not be reproducing.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species’ definitions of vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered are used to encompass the overall concept of being at risk of extinction.

The IUCN Red List is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of plant and animal species. It uses a set of quantitative criteria to evaluate the extinction risk of thousands of species. These criteria are relevant to most species and all regions of the world. With its strong scientific base, the IUCN Red List is recognised as the most authoritative guide to the status of biological diversity.

Currently the IUCN Red List status is that 36% of the 47,677 species assessed are threatened with extinction, which represents:

- 21% of mammals

- 30% of amphibians

- 12% of birds

- 28% of reptiles

- 37% of freshwater fishes

- 70% of plants

- 35% of invertebrates

that have been assessed.

Averaged across all the taxonomic groups of animals and plants that have had IUCN Red List assessments, about 25% of species are threatened. But the sparse data for insects so far suggest it might be lower – estimates range from 10 to 15% – so IPBES used a figure of 10% that might turn out to be conservative. If insects are three-quarters of animal and plant species, there are 5.5 million of them, of which 10% are threatened (so, more than half a million insect species are threatened). If 25% of the other 2.6 million species are threatened, that’s more than half a million non-insect species threatened. Hence the rounded total figure is about 1 million species at risk of extinction.

Are the headlines about loss of species meaningful?

Some very broad assumptions have been used in coming up with the figure of 1 million species at risk of extinction over the next few decades. One wonders if this is a meaningful exercise.

Are people going to take more notice of this announcement?

Is there a better way of illustrating the significance of the threat of massive biodiversity loss over the next few decades?

Maybe the percentages quoted earlier mean more, such as 70% of plants and 21% of mammals?

Another factor that may be more significant is the loss of biomass of plants and animals. Recent studies have pointed to the significant decline in biomass of insects. Dr Sanchez-Bayo from Sydney University pointed this out in a recent paper to the journal Biological Conservation [2].

Besides all the important functions that insects play in our ecosystems - such as pollination, or recycling nutrients - they are also an essential element in the food chain that supports life on our planet. When the insects go, the frogs, birds and mammals don't have food.

The IPBES Assessment is mostly devoted to describing the reasons for species decline and what should be done about it. The reasons are not hard to find: exploitation, land clearing, weed and pathogen invasion, climate change.

Currently biodiversity law and policy is inadequate to redress the situation. If we are to halt the continued loss of nature, then the world’s legal, institutional and economic systems must be reformed entirely. And this change needs to happen immediately.

Reference

[1] Mora, C; Tittensor, DP; Adl, S; Simpson, AGB; Worm, B (2011) How Many Species are there on Earth and in the Ocean? PLOS Biol 9(8): e1001127

[2] Sánchez-Bayo, F and Wyckhuys, KAG (2019) Worldwide Decline of the Entomofauna: A Review of its Drivers. Biological Conservation 232, 8–27

Great Season for Fungi

Our walk in Fox Valley on 14 April revealed some surprises. A Powerful Owl was spotted and there were several unusual examples of fungi as identified by John Martyn.

Calocera or Dead Man’s fingers

Bolettus emodensis

New Committee Member

We welcome Peter Clarke as a new member of the committee. He is well known for his work with Ku-ring-gai Council developing new programs such as the native bee hive rollout (how about coming to the talk he's giving about native bees) and pool to pond. He is a familiar face on the educational videos on EnviroTube.

Peter’s great knowledge of the Ku-ring-gai bushland and his education skills will be a great asset to STEP.

A Short History of the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest

The rainforest corridors along the gullies of northern Sydney have been called by many names as ecologists try to describe them and place them into a broader classification system, for example Temperate Rainforest (1), Sandstone Gully Rainforest (2), Coachwood Rainforest (3), Northern Warm Temperate Rainforest (4) and now more recently Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest (5).

While this rainforest forms a highly recognisable ecological community, the history and evolution of the individual plant species are all quite different.

Mosses and liverworts, not the extant species, were the first land plants and appeared around 470 million years ago (Ma) in the Ordovician. It has been speculated that their impact on the earth caused an ice age because of plummeting carbon dioxide (6).

Jumping forward to the mid Devonian (383–393 Ma) and a new group of plants is present, the ferns. Most of the earliest ferns are now extinct and most of our extant ferns date from only the last 70 million years, the late Cretaceous (7). Ferns of the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest include Common Maidenhair (Adiantum aethiopicum), False Bracken (Calochlaena dubia), Umbrella Fern (Sticherus flabellatus) and tree-ferns (Cyathea species). The origin of the Cyathea tree-ferns goes back to the Jurassic (201–145 Ma) (8) but the diversity in this tree fern family is unlikely to be older than the Palaeocene (younger than 66 million years).

The Umbrella Fern and Coral Fern (Gleichenia species) are considered an ancient fern family and date from at least the early Cretaceous (9) (approx 145 Ma).

Ancestry from millions of years ago: mosses from 470 Ma, Umbrella Fern from approx 145 Ma and Coachwoods from approx 34–28 Ma (photo Robin Buchanan)

The trees that dominate the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest are all flowering plants. The earliest fossil records of a flowering plant date from early Jurassic (10), more than 174 Ma but the diversification and dominance of flowering plants occurred from the Cretaceous (145–66 Ma) to more recent times (11). The main tree families of the rainforest include Myrtaceae, Cunoniaceae and Pittosporaceae.

Myrtaceae is an enormous family that has 1646 species in Australia and 3000 in the world (12). It is also very diverse with dry fruited plants typical of dry sclerophyll, such as Eucalyptus, and fleshy fruited plants typical of rainforests. It is primarily a southern hemisphere family with considerable northern extension. Crown Myrtaceae seem to date from only 95–84 Ma (13) (mid to upper Cretaceous). Species common in the Gallery Rainforest include Narrow-leaf Myrtle Austromyrtus tenuifolia, Grey Myrtle Backhousia myrtifolia, Water Gum Tristaniopsis laurina and Lilly Pilly Acmena smithii.

The Cunoniaceae is a small family with a Gondwanan origin and seems to date back to late Cretaceous. This family includes the trees Coachwood Ceratopetalum apetalum and Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia. Ceratopetalum and Callicoma had evolved by the early Oligocene (34–28 Ma) or earlier (14).

Pittopsporaceae, containing Mock Orange Pittosporum undulatum, seems to have originated in Australasia in the early Cretaceous (approx 117 Ma) (15).

Australia’s rainforests are a mere remnant of their former glory in the early Miocene (c23–16 Ma) when they were wide spread. By the late Miocene (10.5–5 Ma) the drying out of Australia had resulted in forests and woodlands across Australia and the remnants of the rainforests were confined to the wetter coastal areas of Australia (16).

In the northern suburbs there are also smaller stands of Coastal Warm Temperate Rainforest, Coastal Escarpment Littoral Rainforest and Coastal Headland Littoral Rainforest (5) but the Coastal Sandstone Gallery Rainforest is far the most common.

References

- Robinson, L (1991) Field Guide to the Native Plants of Sydney, Kangaroo Press

- Martyn, J (2010) Field Guide to the Bushland of the Lane Cove Valley, STEP

- Smith Ecological Consultants (2008) Native Vegetation Communities of Hornsby Shire

- Keith, D (2004) Ocean Shores to Desert Dunes, NSW NPWS

- Office of Environment and Heritage (2016) The Native Vegetation of the Sydney Metropolitan Area. Vol 2: Vegetation Community Profiles, ver 3

- Marshall, M (2012) First plants plunge earth into ice age New Scientist

- Pinson, J About Ferns American Fern Society

- Bystriakova, N et al (2011) Evolution of the climatic niche in scaly tree ferns (Cyatheaceae, Polypodiopsida) Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 165(1), 1–19

- Gonzales, J and Kessler, M (2011) A synopsis of the Neoptropical species of Sticherus (Gleicheniaceae), with descriptions of nine new species Phytotaxa 31, 1–54

- eLife (2018) Fossils suggest flowers originated 50 million years earlier than thought ScienceDaily

- Foster, C (2016) The evolutionary history of flowering plants Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 149(1&2) 65–82

- Centre for Biodiversity Research (2002) Australian Flora and Vegetation Statistics

- Stevens, PF (2001 onwards) Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, ver 14, July 2017 (and more or less continuously updated since)

- Barnes, R (1999) Palaeobiogeography, extinctions and evolutionary trends in the Cunoniaceae: A synthesis of the fossil record PhD thesis, University of Tasmania

- Nicolas, N and Plunkett, G (2014) Diversification times and biogeographic patterns in Apiales Botanical Review 80(1) 30–58

- Australian Museum (2018) Evolving Landscapes

Photo at the top of the page: dense foliage of Coachwoods and Black Wattle in the rainforest lining the creek between eucalyptus dominated slopes (photo Robin Buchanan)

Robin Buchanan

Caring for Country

The Aboriginal heritage of northern Sydney reminds us that these precious environments around us have been valued and nurtured for thousands of years. It reminds us that people can adapt and survive significant changes in climate. It also reminds us that some things can’t be replaced or regenerated.

It could be said that Aboriginal history has only recently gained a greater following in some parts of the wider community. Modern Australian history as a whole is quite short and it is understandable that a young society would choose to focus on the positives rather than delve into what is uncomfortable. An unfortunate consequence is that when we seek to learn more, the sources of information are fewer and less detailed.

The cataclysmic loss of life as a result of the smallpox epidemic in 1789 also meant a huge loss of traditional knowledge. The following decades of policies and attitudes that were unsympathetic towards Aboriginal people meant that the comprehensive environmental knowledge of the custodians for every tree and flower and hill and creek and bay would diminish.

Much of the work to learn about and protect Aboriginal heritage has focussed on the archaeology. The rock engravings found on Hawkesbury Sandstone platforms among Angophoras and Acacias have intrigued visitors and residents alike.

What could they mean? Macropods and marine species, boomerangs and shields, human and deity figures are represented in different areas.

Some were recorded and discussed in academic journals from the mid-1800s, with names suitable to the era, such as Mankind. A government surveyor recorded hundreds of engraving sites in the sandstone country in the late 1890s.

Throughout the twentieth century various individuals from the Australian Museum and elsewhere researched and tried to urge governments and the wider population to value and protect the engravings. Some engravings were individually protected through this and local activism, as well as the thousands that were deliberately and accidentally protected in the state and local government reserve system. The role of individual Aboriginal people in these campaigns is still poorly researched.

Then there are the rock shelters. Hawkesbury Sandstone again provided a medium for Aboriginal heritage to merge with the environment. What could be a spectacular natural landscape feature could also contain the hand stencils of family members from thousands of years ago, or the painted image of an important animal or its tracks. Even the ones we have forgotten locally, like emus and koalas.

Then there are the shell middens that shine along the now rapidly eroding foreshores of the estuaries and bays of this incredible landscape. Places where families gathered year after year to share food and stories. The middens tell us what people gathered and brought back to eat. They inform us of environmental and cultural change over time with variations in species and quantity. They invite Aboriginal people to feel welcome and connected.

Could it be said that the outsider’s interest in Aboriginal heritage and culture has been aimed in the wrong direction?

What does it matter if we record the engraved images of an animal if we have not recorded the wisdom of how to protect that species or its habitat?

Is it even fair to try to capture that wisdom but not nurture the people who have developed and implemented it over such an incredible period of the earth’s history?

We cannot go back and reinvent the past, only learn from it. Some knowledge that has been lost cannot be recaptured. A rock engraving destroyed or faded away is gone forever. However, as the bush regenerators know, the seedlings that are given the right conditions today will become tomorrow’s resilient canopy.

The climate is changing and the urban bushland is under increasing pressure. The many traditions of looking after one’s local area are more important than ever.

Our thanks go to David Watts and the friendly team at the Aboriginal Heritage Office.

Photo at top of page: David Watts with group on Sites Awareness walk, late 1990s

David Watts

Geology of the Sydney Basin

Our local and regional environment owes so much to its geological heritage. We live in the Sydney Basin, an epicontinental pile of sedimentary rocks several kilometres thick that was laid down in the Permian and Triassic periods between 300 and 200 million years ago, and our present landscape framework was created by tectonic uplift and erosion of its strata.

Abundant life in a chilly sea

We might think of our local landscapes in terms of its multiple sandstone tablelands, spurs and gorges. Their rocks were mostly laid down by fresh and brackish water in flood plains and estuaries, but the early history of the Sydney Basin incorporates a strong marine influence, and you can find abundant shelly fossils in numerous sites along the coast south of Wollongong. There's also much evidence that the sea at the time was icy cold and peppered with drifting, melting icebergs, and you can still view their dropped erratic, morainic boulders nestling amongst the fossils in cliffs and rock platforms. The mineral glendonite found down there only forms today in icy-cold sea floor mud – it was named after its discovery site at Glendon on the Hunter River. The global climate conditions captured by this older Sydney Basin suite is of national significance both to our scientific heritage and to a broader understanding of the earth's history.

A great extinction event

Towards the close of that chilly, early basin epoch, the seas gradually subsided and coal formed from the peat of boreal swamp forests, contributing historically to our region's strong economic base. But the coal story came to an abrupt end 252 million years ago with the great end-Permian extinction event, when massive volcanic outpourings on the far side of the globe bathed the planet in acidic gloom and warmed and dried its atmosphere.

The evidence is beautifully preserved in cliffs south of Newcastle (pictured), north of Wollongong and also in the Blue Mountains.

This key event should be much more widely recognised and understood as its effects are mirrored in current climate change and extinctions. Our local geological heritage carries critically important environmental messages for today.

Plain old sandstones reveal fascinating stories

Some of our local sandstones were sourced from a long way off. Research on the Hawkesbury Sandstone based on radiometric dating has matched grains of a mineral called zircon with the same mineral in igneous rocks of the Transantarctic Mountains. Antarctica was joined to Australia at that time, and while still a long way off, the scale of the river system implicated is well within that of many flowing across present day continents.

Australia's membership of the supercontinents of Pangaea and subsequently Gondwana was the beginning of a story that flows right through to the roots of our floral diversity. Clearly it underpins our natural heritage.

Our sandstone's floral diversity

Our sandstone landscapes are built largely from nutrient poor but iron- and quartz-rich rocks that support an incredibly rich flora, many of whose species benefit from the buffering action of iron against phosphorus toxicity. The floral diversities of sandstone heathlands and shrublands in places like the Royal and Ku-ring-gai Chase are only surpassed in Australia by those of south-west WA, an internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot. Long term, the heritage value of our local bushland outstrips that of any of the temporary creations of human activity, however functional or beautiful they might be, and it must be preserved at all cost.

Dinosaurs, volcanoes and diatremes

The earlier paragraph on the great extinction event might also have mentioned that this kick-started the evolution of the dinosaurs, which of course ultimately led to the birds. The dinosaur era peaked in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods between 200 and 66 million years ago before ending in that other great extinction event, and at that time the sedimentary rocks of the Sydney Basin were compacting and drying out.

But there was still enough water left in their pores and joints that when basaltic magmas trickled in from depth, it flashed it into superheated steam that shattered its way to the surface at numerous points around the region. In many cases the magmas wormed their way through the crevices of shattered rock to follow it to the surface, also to be blown to smithereens by explosive pressures. The volcano style of that time is known as a maar, and its feeding pipe a diatreme.

In our northern Sydney region we have the largest and best preserved diatreme in Australia in the Hornsby quarry. This has heritage value and is a geological site of international status. Fortunately it appears the filling of the quarry for the parkland project has preserved the upper faces and cleared them of debris, thus exposing the diatreme's classic layered structure (pictured).

Layering in the volcanic debris of the Hornsby diatreme

Photo at the top of the page: Ghosties Beach Munmorah: black coal followed by white sandstone band marks the extinction event

Dr John Martyn

Timbergetting in the Lane Cove Catchment

In February 1805 botanist George Caley (sent out by Sir Joseph Banks) made an exploratory trip from Pennant Hills across the upper catchment of the Lane Cove River and reported on the fine timber. Nine months later Governor King issued directions for a gang of convicts to be employed at the North Shore to procure ship timber.

A timber carriage with eight draught bullocks was conveyed to the work site in the government punt, attended by a competent number of hands. Thomas Hyndes, one of the original grantees of land at Wahroonga, and clerk and overseer to the superintendent of camp and gaol gangs, probably accompanied them to the site on the flat at Fiddens Wharf, on the northern side of the Lane Cove River at Killara.

From an administrative point of view the Lane Cove camp was a problem. It was located distant from Sydney and run by overseers who had not been tried and tested in Sydney under the watchful eye of the principal superintendent.

There were three overseers appointed and dismissed from Lane Cove between 1808 and 1814. It was during 1809 to 1814 that the camp was most productive. The main timbers logged were Blackbutt, Blue Gum and Iron Bark for building purposes and Casuarina for roof shingles.

Governor Bligh prepared material to erect some necessary buildings including a large barrack for soldiers and timber from the North Shore Camp was used to build the Parramatta Store, completed by the end of 1809, and the Commissariat Building in Sydney, begun in 1809. These no longer exist.

Macquarie visited the camp in May 1810 and found that the timber in the Lane Cove Valley between Hornsby and Roseville was getting scarce and observed that the camp would need to be moved elsewhere.

Macquarie’s first major project using Lane Cove timber was the building of a Light Horse Barracks and a new hospital, now Parliament House and The Mint. The numbers of draught cattle at Lane Cove were trebled in preparation for this major project.

Rafters at the southern end of The Mint showing a purlin (top horizontal timber) attached to the rafter using a tusk tenon joint (photo Ralph Hawkins)

In 1814 there were two overseers at Lane Cove; one for the men and one for the stock. There were four timber fellers who supplied eleven sawyers, seven shingle splitters, eight timber carriage drivers, four stockmen, two boatmen, two blacksmiths and a wheelwright. There were also two watchmen and five other labourers, making a total of 48 men.

The hospital, completed in 1816, has some of the last timber cut at Lane Cove. Soon afterwards the camp was re-located to Pennant Hills and the North Shore was described as follows by Alexander Harris:

I could not but take notice of the immense number of tree stumps. Each one of these had supplied its barrel to the splitter or sawyer or squarer: and altogether the number seemed countless. Several times I was induced to wander off the road down a grassy slope overshadowed by oak or gum or ironbark, to where I saw the form of a hut, in the hope of getting a light for my pipe; but found only some deserted pit or falling hut, with docks and other such plants growing all around, as is usually the case when the grass has been destroyed to the very roots.

Photo at the top of the page shows timbers in The Mint that were probably sawn from timber cut in Lane Cove during 1812 and 1813; the ceiling joists are all numbered in Roman numerals (photo Ralph Hawkins)

Ralph Hawkins

Annie Wyatt’s Conservation Ethic and the National Trust

Ku-ring-gai has a rich environmental history. Some even consider it to be the birthplace of the Australian conservation movement because it was here that one resident, Annie Forsyth Wyatt, called for a National Trust (NSW) to be founded.

Gordon resident, Annie Wyatt (1885–1961) became a strong force in the emerging conservation movement, collaborating with many other key Sydney conservationists of the 1930s. Annie Wyatt was very insistent that the early National Trust (NSW) be a force in protecting the natural environment:

… to safeguard and govern the national state parks, national monuments and reserves of the state.

Annie Wyatt, grew up when there was deep concern about the loss of many of Australia’s forests. As a young woman she witnessed the ‘wanton destruction’ of the trees, bushlands, forests, woodlands and fine colonial houses on Sydney’s Cumberland Plain, when she lived at Rooty Hill as a young girl.

However, Annie Wyatt became a conservationist ‘activist’ after being incensed when she saw a Ku-ring-gai Council truck dumping garbage into the creek below her home in Gordon in 1927. Distressed, she quickly gathered her neighbours together.

This led to her forming the Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League which aimed ‘to safeguard the natural charms of the municipality’ and in particular to promote Australian native trees.

The League organised school essay competitions and tree planting ceremonies that included celebrating ‘tree lover’ Joseph Maiden (1859–1925), the Director of the Botanical Gardens and a pioneer advocate for eucalyptus forests.

Underneath the magnificent lemon-scented gum tree along Henry Street, Gordon, in the Annie Wyatt Park, next to Gordon Station, lies a plaque dedicated to Mr and Mrs Charles Musson. The Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League planted this eucalyptus in memory of Charles Musson (1856–1928), Gordon resident and teacher-lecturer at the Hawkesbury Agricultural College. Charles Musson was a great enthusiast for the new school subject – nature study – that was being introduced into the school curriculum in the early 20th century.

The Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League inspired others to form their own tree lovers’ leagues in places such as Lane Cove, Mosman and Orange.

Annie Wyatt and the Ku-ring-gai Tree Lovers’ Civic League, went on to work with many other conservationists in the 1930s including Charles Bean (1879-1968), revered WW I war correspondent and historian, and founder of the Parks and Playground Movement. Charles Bean was active in promoting the green-belt around Sydney with parks and playgrounds including the Lane Cove and Garigal National Parks (former Davidson).

David G Stead (1877–1957), the founder of one of the first organisations to protect native wildlife (the Wildlife Preservation Society) in 1909, was supportive of Annie Wyatt’s motion to form the National Trust at the Save the Trees Conference in 1944. This conference arose from the deep concern about the massive clearing of forests happening across the country.

Annie’s son Ivor Wyatt (1915-2004) followed his mother’s conservation efforts, and became president of the National Trust working with David G. Stead’s wife, botanist and teacher-lecturer Thistle Y Harris (1902–90), to promote the flora and fauna sanctuary and environmental education centre – Wirrimbirra – at Bargo.

Annie Wyatt, was an unashamed ‘ardent tree lover’. She rejected the notion of ‘progress’ that emerged as the dominant ethos after WW II that demolished swaths of colonial buildings and land cleared massive bushland across the state.

When Annie Wyatt formed the National Trust of NSW in 1945 she wanted an organisation that would protect monuments, houses and landscapes for perpetuity. She modelled it on the English National Trust which was fighting to protect its own significant buildings, monuments and landscapes from being destroyed by encroaching industrialisation towards the end of the 19th century.

The National Trust became an important counter voice opposing the post war calls for modernity and ‘progress’ that was knocking down so much history and nature.

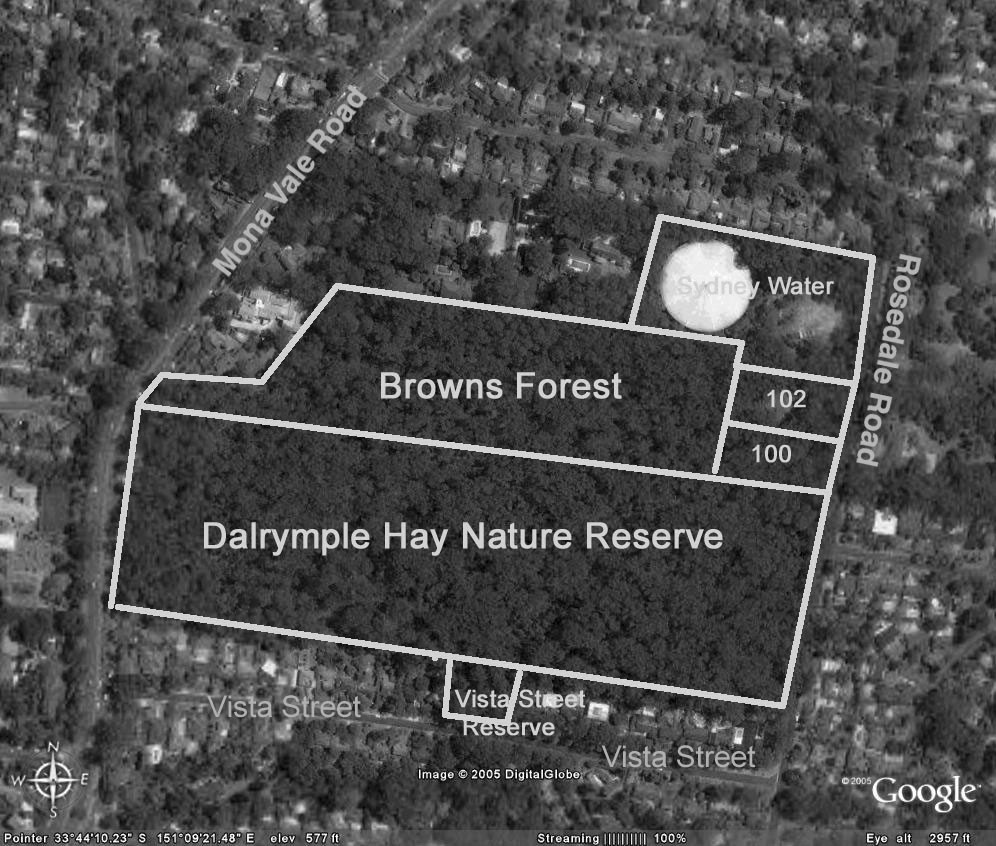

When Annie Wyatt saw the threat to the Dalrymple Hay Forest on Mona Vale Road, Pymble/St Ives in 1934 she worked with the ‘tree mayor of Ku-ring-gai’, Cresswell O'Reilly (1877–1954) to raise funds to purchase 11.5 acres to prevent the subdivision of Dalrymple Hay Forest, Mona Vale Road, St Ives in 1934. Cresswell O’Reilly would go on the chair the first meetings of the National Trust of Australia (NSW) formed in 1945.

Professor Eben Gowrie Waterhouse (1881–1977), of Eryldene, Gordon, also supported Annie Wyatt in this Ku-ring-gai forest campaign and presented the petition to save the Blue Gum High Forest to Ku-ring-gai Council. The community was again galvanised into campaigning to protect this unique and precious forest when it was again threatened with development from 2004–07.

Annie Wyatt’s conservation ethic continues to this day in the fight to protect Sydney’s urban bushland.

Photo at the top of the page is of the Tree Lovers’ Civic League planting in 1949 (courtesy National Trust of Australia (NSW) Archives)

Janine Kitson

Ahimsa: A Story of Bushland Protection

Walking along hand built stone paths into the bushland property Ahimsa is a step back in time and an inspiration for the future. It is also a remarkable testament to the former owner Marie Byles.

Gifted to the National Trust of Australia (NSW) over 40 years ago by Marie Byles, this 3.5 acre bushland property at Cheltenham in the Upper Lane Cove Valley is now listed as a state heritage item. Ahimsa adjoins Lane Cove National Park and is part of a large area of bushland surrounded by urban development.

Marie Byles was a visionary woman well ahead of her time. She was the first female to practice law in NSW, a mountaineer, explorer and avid bushwalker, a committed conservationist, a feminist, author, and original member of the Buddhist Society in NSW.

Marie was a passionate protector of bushland, whether from development, roads, weeds, or uncaring government officials. In 1938 she built a simple fibro and sandstone cottage on the property for her home on a rock ledge overlooking the beautiful surrounding bushland. The name of her home Ahimsa means harmlessness, a Buddhist and Hindu spiritual doctrine and Sanskrit word. This name reflects her belief that we are not separate from the world around us, and the natural environment should be respected and protected from harm.

Later in 1947, Marie designed the nearby Hut of Happy Omen which was built by friends and volunteers to accommodate a range of people and activities, including visiting Buddhists, bushwalking groups, conservationists and social gatherings.

Ahimsa is little changed in over half a century, and represents the physical expression of the life and values of Marie Byles. She left the land to the National Trust to protect its bushland in perpetuity, and in the public interest. The significance of the property is its realisation of Marie’s lifestyle and beliefs, and strong connection with current ideas about sustainable living, mindfulness, meditation and protection of the natural environment.

Ahimsa is a place that is important in the story of the conservation of Sydney’s bushland. An easy walk from the railway station, it is a place of peace away from Sydney’s hustle and bustle. The Hut of Happy Omen is available for use by people and groups compatible with the values of the property, by arrangement with the National Trust.

Friends of Ahimsa is working with the National Trust of Australia (NSW) to support future management of the property and to make Ahimsa accessible as a place that tells the story of its former owner and contributes to the realisation of Marie Byles’ dreams and values.

Children’s Art at Ahimsa on Sunday 28 April 2019 provides an opportunity for children between 7 and 11 years of age and their carers to appreciate the Ahimsa bush.

Although Ahimsa faces challenges for the future, including how to effectively maintain its bushland, heritage values and buildings, Marie Byles’ vision of simple living and protection of nature remains an inspiration. It is hoped that future generations will continue to use Ahimsa to learn about and reflect on Sydney’s bushland heritage, and the people who were instrumental in protecting it.

To find out more about Friends of Ahimsa, the conservation and management of the property, or to be placed on the Friends of Ahimsa contact list for future events and activities, please email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Martin Fallding has a lifelong association with Ahimsa as a neighbour and family friend of Marie Byles. He has had a long involvement in bushland conservation and is currently the president of Friends of Ahimsa.

Camps for Girls at West Head in the 1950s

1956 was my second year out from Sydney Teachers’ College where I trained as a physical education teacher. As a young 21-year-old I was very excited to get the opportunity to apply to be seconded from the NSW Education Department to the National Fitness Council programme. The boys’ programme was run at Juno Head and Little Marley. The girls’ programme was at West Head where an army base had been built during World War II.

The programme ran from Tuesday to Thursday for one or two schools each week. A teacher from each school was asked to attend, but this seldom happened. Generally, I would have about 20 girls, but I recall one time when I had 44 girls on my own!

On Tuesday morning at 9 am the girls would come to the Nat. Fit Office with their food and clothes. I would issue each of them with a Paddy Pallin four pocket A frame canvas backpack and an ex-army groundsheet. I would then show them how to pack their tins of food and usually an enamel plate and mug.

We would then all set off to walk to York Street to catch the double decker bus to Palm Beach. The trip took an hour and a half to the old wharf on Pittwater where we caught the 12 o’clock ferry to Big Mackerel Beach. Then it usually took about one and a half hours to walk up to camp which was about 300 feet above sea level. The girls used to find it hard going as their packs often had tinned food and they were not familiar either with a bush track or carrying a backpack.

It was a very pretty walk as it wound around the steeply sloping hillside of excellent Hawkesbury sandstone flora looking opposite to the Barrenjoey tombola. Just before the final climb up to West Head there was a waterfall which had to be negotiated by sidling along a narrow ledge.

It was a steep climb up the last 150 feet to the camp at the top where a tired group of girls would be greeted by the camp caretaker Stewart Pitts and Mrs Pitts. A retired couple who had built a cottage in Big Mackerel Beach. Both had a broad Scottish accent and they always had a cup of tea in their kitchen for me.

There was no electricity at camp apart from a generator that supplied lights at night. Perishables were put in a kerosene refrigerator. The girls slept in a 30 bed dormitory of former army bunks which had a horsehair mattress on a wire base. At the southern end there was had a huge fuel stove which I recall I had to use on a couple of occasions when it was too wet to cook outside. It was extremely smoky when the fire was lit.

When they were all settled in we would have a short walk to gather firewood up the dirt road towards Commodore Heights. I would explain some of the early European history to explain where all the names came from and show them remnants of the old military occupation during World War II, when over 500 men were stationed to protect the important rail and road bridges further up the river, linking Sydney with industrial Newcastle and its strategically important steel works.

The views were and still are magnificent, looking north up to Gosford and the Central Coast, and opposite to the striking Barrenjoey Lighthouse and the old Custom House on Pittwater.

After gathering firewood for their group, they learnt how to make a tidy wood pile and later how to build a cooking fire in the grates provided near the great rock outcrops on the western side of the mess hall. As many of the girls were from inner city areas, camping and outdoor cooking and washing up were not familiar tasks.

The toilet was a pit toilet or ‘long-drop’ at the end of a pathway back from the camp. The huge septic tank from the wartime was not available then. Water came from a tank.

The first evening we had team games in the mess hall. Lights out was at 9 pm. For many of the girls going to the toilet after dark was quite scary; as were all the strange animal calls at night, especially when possums had an argument on the tin roof. For many, they had not been away from street lights and there were no outside lights at the camp. Settling down at night was quite a challenge for some!

On our second day we went out bushwalking for the day to see Aboriginal engravings or to visit the many delightful creeks, or beaches on the Hawkesbury River. Flint and Steel and Hungry beach being favourite places.

Usually we would see a koala in the trees on Commodore Heights. There was so much of interest in the history and in the vegetation and wildlife. Occasionally, we would scramble down under the old camouflage nets and steep wooden stairs to the gun emplacements near the shoreline of the river. By about 3 pm I would aim to be back at camp to gather firewood for a campfire. Making doughboys, campfire singing and skits prepared by the girls were our evening entertainment.

On the last morning after breakfast we had a general clean-up, then we retraced our steps back down to the ferry at Mackerel Beach, then across to the city bus and a walk to Bridge Street after a great time at Three Day Camp.

In retrospect, this was a great time for nature-based learning and for appreciation of our potential World Heritage, Sydney Basin Sandstone Flora and Fauna. Since the National Fitness Office was taken over by the Department of Sport and Recreation, I feel that school education has lost its appreciation of local geology, flora and fauna-based learning which was then available to a few.

Sadly, schools have generally lost the experience of the joys of bushwalking, and the intrinsic mutual benefits of understanding how our natural heritage and our human health and well-being are inter-connected with the health and well-being of our unique natural heritage.

Click here for an interesting history of pre-war attempts to develop West Head. We are thankful that appreciation of our bushland has changed!

Click here for an account of West Head’s World War II history.

Janet Fairlie-Cuninghame

Time for Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park to be World Heritage Listed

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is part of a geographic, geologic and eucalyptus sandstone bushland arc that encircles Sydney. This 12,963 hectare national park is on the Hawkesbury Sandstone Plateau of northern Sydney. It is connected via other national parks to the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, which in turn is connected to the Royal National Park, south of Sydney.

The Sutherland Shire Environment Centre have been campaigning for the Royal National Park to be World Heritage listed for some time. They argue that the Royal has such cultural heritage importance as it marks the beginning of the global national park movement. The Sutherland Shire Environment Centre even argue that the Royal is the first national park in the world because it was the first to be called The National Park. US’s Yellowstone (1872), used the term ‘national park’ to acknowledge that it was administered by the federal government and not the state government.

Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park is also one of the first national parks in the world to be formed for the intrinsic value of nature. In 1894, it was the second national park declared in NSW. Its corporate seal – Natura Ars Dei or Nature is the Art of God – also expresses a spiritual connection to nature.

The driving force behind Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was Eccleston Du Faur (1832–1915), a 19th century national parks advocate, adventurer and patron of the arts.

Eccleston Du Faur belonged to the 19th century Sydney intelligentsia and cultural elite who supported the creative endeavours of artists and explorers who ‘believed’ in this new land. Although born in England, du Faur was awe struck by the sandstone beauty of the Blue Mountains and Ku-ring-gai Chase. He played a key role in protecting the Blue Mountains’ Grose Valley because he believed it was one of the most beautiful places in the world.

In 1875 he employed the photographer, Joseph Bischoff, to join him, along with artist WC Piguenit, on an expedition to sketch, paint and photograph the Grose Valley, near Govetts Leap Falls. He planned to send Bischoff’s photographs to the 1876 Centenary Exposition in Philadelphia, USA. He wanted the world to see the Blue Mountains because he believed its spectacular scenery was unrivalled and even surpassed Yellowstone National Park in beauty.

Du Faur was also concerned about Sydney’s fastly disappearing wildflowers and made sure the park’s first by-laws had laws against the cutting of wildflowers. Regretfully this was not strong enough to stop the removal of 4000 waratahs, taken in one month in the post WW II years. The Trustees also prohibited the defacement and destruction of Aboriginal rock art sites and middens in the park.

Recently the Friends of Ku-ring-gai Environment (FOKE) have met with STEP to discuss how they can work together in putting forward the claim for World Heritage listing Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park – one of the first national parks in the world.

Janine Kitson

The Early Days in what is now Lane Cove National Park

The early European history of the area that became Lane Cove National Park could be said to stem from an exploratory visit to the Lane Cove River by George Caley in 1805. Caley was employed as a plant collector by Joseph Banks and was the first person to make a systematic study of eucalypts. He reported on the quality of the trees in the Lane Cove River valley and it is thought that as a result a convict timber camp was set up at what later became Fiddens Wharf.

One of the convicts employed at the camp was William Henry. He arrived in 1801 on the Earl Cornwallis, and no doubt obtained a good knowledge of the valley while working as a timber getter. After Henry was emancipated Governor William Bligh promised him a grant of 1,000 acres in an area which now includes much of the lower park and West Lindfield. Henry took up the grant and started a vineyard on a portion of the area. Unfortunately for him Bligh became somewhat distracted with the Rum Rebellion, the grant was never confirmed and eventually around 1850 Henry was thrown off the land as the government of the day prepared to sell it.

Some say that another famous Australian identity, John MacArthur had schemed to ensure that William Henry suffered because he had supported Bligh during the rebellion.

However, that was not the end of his family’s connection, his granddaughter Maria married Thomas Jenkins and in 1852 they purchased a portion of the land originally held by her grandfather. It was this family who held the property right up until 1937 when it was purchased by the government to form the basis of the national park.

The farm or orchard was known as Millwood, the house Waterview and the small stone building we now know as Jenkin’s Kitchen was built around 1855, separately from the house, as was often the case at that time when there was a fear of fire burning down the main building. Ironically the main building burnt down in 1943 after the incorporation of the area into the park, and although the kitchen has been affected by fire it is still with us.

After the recent renovations, which include a new roof and extensive work to the sandstone, there is every hope that it will remain as a focal point at the park headquarters for many years.

Invitation